di Arnold Cassola [*]

When Garibaldi landed in Marsala with his mille on 11th May 1860, fighting immediately started in the western part of Sicily. The unification process of Italy was well on its way. In the 19th century news did not travel very fast, but of course the population living in that part of Sicily soon got to know of Garibaldi’s exploits.

The same cannot be said for all parts of Sicily. How fast did news travel at that time to the more remote parts of the island? The scope of this work is to show that in fact, as regards the town of Modica, which is to be found in the South Eastern part of Sicily, and today falls under the province of Ragusa, a relevant amount of information regarding Garibaldi’s progress on the island as well as other related activity actually arrived in Modica via telegrams which were sent from the island of Malta, which lies around 164 kms. to the south of this Sicilian town.

The texts of some of these telegrams are to be found today in the section entitled Corrispondenza e scritture varie del periodo risorgimentale (1856-1861) of the Archivio De Leva, Archives of Ragusa, Sezione di Modica. Many of them have been collected and reproduced in the thesis entitled Con il vangelo e la croce in mano – Vita dell’Abate Giuseppe de Leva Gravina (1786 – 1860), which was presented at the University of Perugia in 2003 by Rosario Distefano. Another work on the Abate De Leva’s political involvement is the thesis entitled Il Risorgimento in periferia. L’abate De Leva e le lotte politiche a Modica (1812-1861), presented at the University of Catania in 1986 by Teresa Maria Caruso.

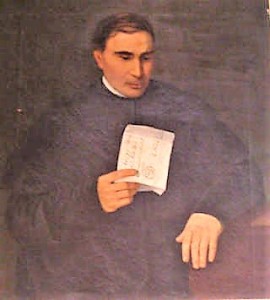

Abate Giuseppe de Leva

Abate Giuseppe De Leva Gravina (1786 – 1861) is the most renowned of the De Leva family. Born in Modica into this aristocratic family, he was given an education largely based on the precepts of liberalism and empiricism. In 1812 he was one of the two deputies elected from the district of Modica to the Sicilian Parliament. In 1837 he took part in the failed insurrections clamouring for independence. In 1848 he was again at the forefront of the uprisings in Sicily, so much so that he became the President of the Comitato rivoluzionario for about a year. As a result of of his political activity, he was suspended by the Bishop of Noto from all religious activity.

However, despite supposedly retiring to private life, the Abate de Leva continued to take part secretly in Risorgimento activities, until he became President of the Comitato Generale set up in Modica. He was tasked with coordinating affairs with the other towns and cities of the area following Garibaldi’s landing in Marsala in May 1860. He died on 21st March 1861. The section of the collection entitled Corrispondenza e scritture varie del periodo risorgimentale (1856-1861) contains various letters and other documents which shed light on the Risorgimento activity in the South-Eastern part of Sicily, but also reveal the role that Malta played in the Risorgimento vis à vis the town and inhabitants of Modica (Iozzia 2008:55-56).

Why Malta?

Why Malta? At that time the island was a colony of Britain. Following the various uprisings in the Italian peninsula, and especially after the failed ones in 1821 and 1848, Malta became home to hundreds of Italian patriot-intellectuals, who fled their home country and continued their fight for freedom and unification from the little island at the centre of the Mediterranean(Bonello-Fiorentini-Schiavone 1982).

The first wave of exiles from the nearby peninsula had forced the British authorities in Malta to review and revise their political strategies. In fact, once these newly arrived immigrants were clamouring for total independence from foreign domination on Italian soil, they actually ended up fighting their battle against the traditional enemies of the British Empire, namely the Papal States in central Italy and the Austro-Hungarian and French empires in the north.

Since a ‘weak’, unified Italy was much less of a threat to British dominance in the Mediterranean than a divided Italy under ‘strong’ foreign rule, the British in Malta decided to support the Italian refugees on the island. One way of doing so was by granting freedom of the press in Malta on 15th March 1839 (Cassola 2000: 186-198).

In view of this possibility of being able to freely propagate their political literature and propaganda, and using their native language, since Italian was the language of the intelligentsia and cultural and political elite of Malta, the activity of the Italian exiles knew no limits.

Apart from a few newspapers written in English and others written in Maltese (Cassola 2011), in the period 1803-1870 the well over one hundred different newspapers written in Italian and printed in Malta were then sent over to the nearby island and peninsula. Moreover, communication between Malta and Modica was also facilitated through the setting up of a telegraph line between the two localities around 1857. This telegraph line at that time «era sotto la dipendenza degli inglesi» (Grana Scolari: 20).

The unhindered flow of newspapers printed and published in Malta and then sent over to nearby Sicily, together with the free flow of information from Malta to Modica and vice-versa via the new telegraph line, is witness to a very open border between Malta and Sicily. This openness not only allowed the possibility of transferring concrete physical objects, like newspapers and weapons, from one island to the other, but also brought about the exchange of ideas and ideals amongst intellectuals living on both sides of the Mediterranean shores, ideals mainly pertaining to the romantic nationalistic philosophy of the Risorgimento period.

It was also by means of telegrams that one could communicate quickly with one’s brothers in arms in nearby Sicily, as can be gathered, e.g., from an undated and unsigned telegram by “Il Capo della Forza di Piazza [Armerina]” to the Abate De Leva, asking for information regarding the postal ship to Malta: «La prego dirmi se è giunto in Malta il vapore postale e quale notizie hanno portato. Piazza 2. ore 8.30 ant. m.» (Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 4).

The existence of a telegraph connection between Modica and Malta enabled inhabitants of other parts of Sicily to be able to communicate expeditely with the authorities in Malta. For example, Francesco Giardina (1818-1899) who, at the time, was one of the leading figures of the Risorgimento in Modica, a follower of Mazzini, and therefore a staunch republican and a sworn enemy of the Bourbon government, could keep his fellow insurgents in Catania informed of what was happening in the rest of Sicily through telegrams «che gli pervenivano telegraficamente per la via di Malta. Così in Catania fu saputa l’entrata di Garibaldi in Palermo e gli eroici trionfi della Capitale» (Belgiorno 1985: 188).

Moreover, proof that the direct contact between Malta and Modica must have been a regular one can be found in the statement of accounts entitled Sovvenzioni, Gratificazioni, ed altre spese (Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 5), which was signed by Raffaele Muccio, who registered all money spent by the Comitato. The above mentioned accounts record, for example, that a Maltese staffetta (couriers/messengers between Malta and Modica) was given 12 tarì on account (“Alla staffetta maltese in conto 12 tarì”) while the repairs needed for eight rifles were entrusted to a Maltese person, who was paid the handsome sum of 3 onze and 15 tarì (“Per acconciare n. 8 fucili al Sig. Maltese 3 onze 15 tarì”).

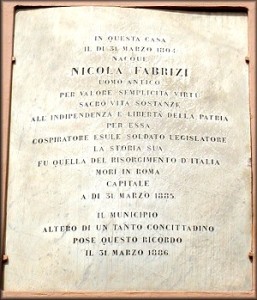

Nicola Fabrizi

Nicola Fabrizi (1804-1885), the famous Italian patriot who was close to Mazzini and the Bandiera brothers and had fought in Italy alongside Ciro Menotti, had first arrived in Malta on board the British ship Firefly on 1st November 1837. In Malta he became the undisputed leader of the Giovine Italia and he strived to spread his revolutionary republican ideas through the setting up of various “reading rooms”. He also set up a business concern together with his brothers, the “Ditta Carlo Fabrizi e Fratelli”. Fabrizi was convinced that the unification of Italy had to start from the south and therefore he was often away from Malta to meet and deal with other Italian migrant revolutionaries in other Mediterranean areas, such as Corfù, Bastia, in Corsica, and Marseilles.

On the outbreak of the 1848 uprisings in Sicily, he went to fight alongside the insurgents and then proceeded first to Venice then to Rome to combat the papal troops. With the fall of the Roman Republic, he tried to return to Malta on 15th July 1849, together with another 123 exiles, but the British Governor of the time, Richard More O’Ferrall, did not authorise the landing. Fabrizi could not set foot again in Malta until November 1853.

In Malta, he tried to gather weapons and munitions for the insurgents in Italy and, as from 1859, he started travelling to and from Malta on a regular basis. In 1860, together with twenty five volunteers, he crossed over to Sicily to join Garibaldi in his quest and to hand over the weapons collected in Malta. This list of twenty five includes the Maltese Giorgio Balbi and Giuseppe Camenzuli.

Fabrizi’s last visit to Malta was in February 1864, i.e. after the unification of Italy. A few weeks later, on 23rd March, he welcomed Giuseppe Garibaldi to Malta. The Italian hero came to Malta for a few days. Whilst he was greeted as a hero by the majority of the Maltese people, Garibaldi was also criticised and insulted by another section of the population (Cassola 2007: 7-16). Nicola Fabrizi left Malta, never to set foot on it again, on board the ship Campidoglio, on 3rd May 1864 (Bonello- Fiorentini-Schiavone 1982: 198-199).

Nicola Fabrizi and Abate Giuseppe De Leva Gravina

The De Leva Gravina Collection hosts five letters by, or concerning, Nicola Fabrizi to the President of the Comitato in Modica. A first undated, unsigned and incomplete letter sent to the Abate De Leva reads:

Signore,

Con questo mio officio le invio otto individui nostri connazionali, i quali son venuti meco in Pozzallo precedendo d’un giorno la piccola spedizione sotto gli ordini del sig. Nicola Fabrizio.

Dovendo io qui rimanere ancora qualche giorno, dove ho ad adempiere altra missione affidatami dal Generale Garibaldi, non potendole accompagnare personalmente, le raccomando alla sua benignità e protezione.

Dessi attenderanno costà l’arrivo del loro capo Sig. Fabrizio, il quale mi lusingo si verificherà in giornata.

Gradisca i sensi della mia stima

(Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 10)

The reference here is to eight individuals “connazionali”, who had arrived in Pozzallo the day before the arrival of another group of exiles, led by Nicola Fabrizio (sic!). While this episode would therefore have occurred before the 21st March 1861, the date of death of Abate De Leva, it is not easy to pinpoint the exact period referred to, since Nicola Fabrizi, who had been living in Malta since 1837, had made various expeditions from Malta to Sicily and the Italian mainland, during his 27 year stay in Malta.

However, the words “Dessi attenderanno costà l’arrivo dello loro capo Sig. Fabrizio, il quale mi lusingo si verificherà in giornata”, together with the fact that the De Leva collection is in possession of two letters by Fabrizi to De Leva dated 5th and 6th June 1860, and sent from Pozzallo, where Fabrizi had just landed from Malta with a number of his followers, points towards the early days of this month as the possible period when the above undated letter was sent, possibly the 5th June 1860 (see letter below).

Whatever the date of this first letter, it is already quite evident here that the possibility for Italian exiles to leave Malta for neighbouring Sicily during the fight for the unification of Italy was quite easy, also because the ruling power in Malta, Britain, was wilfully closing an eye to such activity.

Another undated letter from the “Presidente del Comitato di Noto a quello di Modica” notes that “Inteso che se ci occorre affare il Sig.re Fabrizj è in Modica o Pozzallo. Grazie” (Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 4). The two letters signed by Nicola Fabrizi are instead clearly dated. The first of these two letters sent by Fabrizi to the Abate De Leva, dated, 5th June 1860, and sent from Pozzallo, where he had just landed, reads:

Pozzallo 5 Giugno 1860

Signor Presidente

Prendo la libertà di pregarla, acciocché voglia degnarsi di telegrafare in Noto, che se mai si cercasse da taluno la mia persona, ne l’avvisassero subito perch’Ella con la stessa prestezza me ne tenga informato, mentrecché ho dato quel punto per convegno ad interessanti mie relazioni.

Nell’avviso che va Ella a dare, si compiacerà di manifestare la mia assenza, ed il punto dove io sono.

N. Fabrizj

(Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 10)

In this first letter, Fabrizi asks the Abate De Leva to inform insurgents in Noto of his arrival in Pozzallo and also to let him know if any of them eventually desired to meet or communicate with him. The second letter, dated 6th June 1860, reads:

Pozzallo 6 Giugno 1860

Di mezzo alle sentite dimostrazioni del vostro affetto al mio arrivo de’ miei compagni, io ho creduto mio primo dovere quello di manifestarvi la bella impressione che ne ho ricevuto, e la memoria che saprò tenerne.

E tuttocché né io né i miei compagni crediamo di averle personalmente meritati, abbiamo in esse ammirato il maggiore vostro zelo per la causa che ne ha spinti, e per quella sospirata attuazione della reale unità del nostro Paese moralmente espressa nel novero de’ Giovani che mi hanno seguito, e che vi ho presentato.

Non è a dire del dolore che io sento per essere ben tardi in mezzo a Voi, ma questa tardanza è legata a caggioni contro le quali si è inutilmente lottato. Tuttavia il nostro nemico è ancora fra noi, e noi speriamo con l’anima d’incontrarlo; che se assai presto, com’è il voto di tutti, avrà esso sgombrato questo terreno, noi vi assicuriamo di unire le nostre forze a quelle gloriose dell’Isola, e seguirlo per tutto, rendendo in tal modo ai fratelli del Continente la degna mercede di quanto hanno essi pratticato per noi.

Compiacetevi di far gradire agli onorevoli membri di cotesto Comitato, questi sensi della mia timidezza e dei miei. – Assicuratevi, in ricambio del vostro, e finché avrò vita, del mio affetto.

N. Fabrizj

(Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 10)

Here, Fabrizi thanks De Leva and all the members of the Modica Comitato for the kind hospitality received after landing in Sicily. However, he also expresses his suffering at not having been able to go to Sicily earlier, due to the circumstances – still left unexplained – against which he had fought unsuccessfully. Fabrizi affirms his strong intention of joining forces with all the “gloriose forze” in Sicily in order to chase the common enemy out of island, thus rendering a service to all the insurgents on the mainland, the “fratelli del Continente”.

Another letter sent on the 9th June by Francesco Giardina to Abate de Leva reproduces the text of a third letter received from Nicola Fabrizi on the same day.

Modica li 9 Giugno 1860

Signore

Con la data d’oggi stesso ricevo dal Sig.re Fabrizi il seguente officio: “Sig.re F. Giardina Presidente del Comitato di Guerra in Modica, Mi onoro sottomettere alla di lei autorità che trovandomi nella necessità di condurre un convoglio di generi di guerra da Pozzallo a Noto, sento il bisogno dell’autorità locale per essere proveduto di mezzi di trasporto, non che di una scorta adeguata all’uopo per la garanzia dell’anzidetto convoglio.

Calcolando il materiale da trasportarsi vedo che il bisogno di mezzi sarebbe o di n. 24 carri o di 44 vetture da soma.

Sarà compiacente quindi provedere al bisogno disponendo che i trasporti li recassero in Pozzallo nel corso del giorno di domani.

N. Fabrizi”

L’ho comunicato quindi a Lei perché desse le opportune disposizioni.

Il Presidente

Francesco Giardina

On 9th June, therefore, Fabrizi was requesting the help of the Modica committee in order to be able to transport «un convoglio di generi di Guerra» from Pozzallo to Noto on the following day. These must have been the weapons and other military provisions brought over from Malta, and indeed it must have been quite a substantial amount since Fabrizi calculates that around “24 carri” or “44 vetture di soma” would be needed to transport all the material. Moreover, in order to guarantee the safe arrival of this convoy, Fabrizi was also asking for a number of men to escort and protect the convoy.

A note on the margin of the letter, possibly written by the Abate De Leva, confirms the Modica Comitato’s readiness to fully accede to Fabrizi’s request, even though it must have been received quite late in the day, as can be gathered from the said note:

È stato riscontrato in visto coll’osservazione che l’ufficio presenta la data del 9, lo che ritarda a quanto il Sig. Fabrizi dimanda, ma che intanto subito col noto zelo si adempisse provedendo il Presidente e il comitato di guerra. In riguardo alla richiesta garanzia del convoglio potrà valersi dei soldati d’arme, oggi in parte al servizio della comune.

(Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 5).

In the already mentioned Sovvenzioni, Gratificazioni, ed altre spese (Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 5), one comes across three entries that concern requests made by Fabrizi and which, in some way, confirm that these requests had been acceded to In fact, one entry reads: «Carretto che portò la robba di Fabrizj, e Castiglia», at a cost of 8 tarì; another one “Carrozza per il Pozzallo per Fabrizj” (cost: 24 tarì), and a third one: «Altra [carrozza] per Noto con Fabrizj», which cost the sum of 1 onza and 18 tarì.

Other entries entitled “Carretto per trasportare le armi del Pozzallo”; “Per tre persone a cavallo venute da Pozzallo”; “Diece Carrozze per Pozzallo ai medesimi [emigrati]”; “N. 9 Carretti per prendere fucili, e polvere, ed altri armi al Pozzallo”; “Colazione a quelli che andarono in Pozzallo per i fucili” and “Due Carretti per trasportare le Armi del Pozzallo, e spesa fatta ad Ammatura” could possibly also be linked to Nicola Fabrizi’s request.

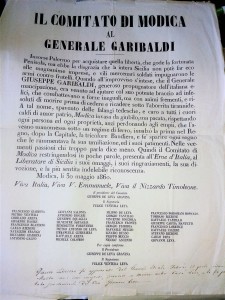

What is certain is that on his arrival from Pozzallo to Modica, Nicola Fabrizi was immediately given a literary-linguistic task by the members of the Modica Comitato. In fact, the Indirizzo a Garibaldi, of 30th May 1860, prepared by the Comitato di Modica, had actually been revised and approved by Nicola Fabrizi, who had recently arrived from Malta. A handwritten note on the printed manifesto (see photo) reads: «Questo indirizzo fù approvato dal Generale Nicola Fabrizi, il quale reduce da Malta con i suoi emigrati, trovavasi in Modica nella Casa Leva, e le fù presentato per esaminarlo dal Cav. Giovanni Leva» (Archivio De Leva, Busta 5/5, fasc. 1).

This last episode clearly summarises the qualities of the man: on the one hand the rebellious warrior fighting for a unified country, on the other, the man of letters ready to provide a helping hand with the drafting of the eulogy prepared for the exaltation of the “eroe dei due Mondi”, Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Being “Intellectual” as well as a “patriotic insurgent” were the two facets of many of the Italian exiles based in Malta. The open border between the two Mediterranean islands allowed these Italian patriots to survive and thrive by furthering their mission in Malta; these same open borders gave the possibility to Maltese intellectuals and patriots to be influenced by their Italian guests, thus being imbued by those same romantic-risorgimento ideals that were to fuel Maltese nationalism as from the 1880s onwards.

Dialoghi Mediterranei, n. 50, luglio 2021

[*] Abstract

Quando Garibaldi sbarcò a Marsala con i suoi Mille l’11 maggio 1860, i lavori preparatori per questa spedizione erano stati eseguiti in anticipo a Malta. La comunicazione tra le due Isole fu anche facilitata dalla creazione di una linea telegrafica tra Malta e Modica intorno al 1857. Il confine era aperto anche in senso fisico. Attraverso la corrispondenza tra l’esule Nicola Fabrizi e l’Abate Giuseppe De Leva, che fu presidente del Comitato rivoluzionario di Modica per circa un anno, si può avere un’idea chiara di come, nel 1860, le armi fossero facilmente contrabbandate da Malta governata dagli inglesi alla vicina Sicilia per fornire agli insorti le armi necessarie.

References

Belgiorno, Arnaldo, 1985, Memorie storiche e uomini illustri della Contea di Modica, Modica: Franco Ruta Editore.

Bonello, Vincenzo; Fiorentini, Bianca; Schiavone, Lorenzo, 1982, Echi del Risorgimento a Malta, Milano: Cisalpino-Goliardica.

Cassola, Arnold, 2000, The Literature of Malta: an Example of Unity in Diversity, Malta: European Commission & Minima Publishers.

Cassola, Arnold, 2007, Garibaldi, Capuana, Rizzo – Due italiani a Malta, un italo-maltese a Tunisi, Roma: Camera dei Deputati.

Cassola, Arnold, 2011, Lost Maltese Newspapers of the 19th Century, Malta: Tumas Fenech Foundation for Education in Journalism.

Grana Scolari, Raffaele, 1895, Cenni storici sulla città di Modica, vol. II. Modica: Tipografia Carlo Papa.

Iozzia, Anna Maria (ed.), 2008, Archivio di Stato Ragusa e Sezione di Modica, Viterbo: Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali and Beta Gamma Editrice.

______________________________________________________________

Arnold Cassola, accademico e politico, ha insegnato nelle Università di Catania (1981-83) e Roma La Sapienza (1983-88). Dal 1988 insegna Letteratura Maltese comparata presso l’Università di Malta, dove ricopre il ruolo di Professore Ordinario. Si interessa di migrazione maltese in Sicilia e in Tunisia, Relazioni culturali italo-maltesi, Storia della Lingua Maltese, Letteratura maltese comparata, e Studi Maltesi in generale. È autore di numerose pubblicazioni. Come politico, Cassola, che ha la doppia cittadinanza malto-italiana, è stato eletto due volte Segretario Generale a Bruxelles del Partito Verde Europeo (1999-2006), e parlamentare alla Camera dei Deputati di Montecitorio (2006-2008), come Italiano all’Estero.

_______________________________________________________________