Abstract [I rivoluzionari e l’eredità europea nella definizione di Stato laico in Egitto]

Sono emerse narrazioni contrastanti circa la natura dello Stato egiziano tra il gennaio 2011 e il luglio 2013. Il regime sostiene di essere impegnato a combattere lo schieramento politico islamo-laico per il controllo dell’ordine pubblico, così da cooptare entrambi i campi e consolidare la propria autorità attraverso le Costituzioni del 2012 e del 2014. I rivoluzionari, che comprendono i diversi gruppi partecipi dei movimenti popolari e degli avvenimenti che hanno portato alla caduta di Mubarak, sono stati emarginati dai luoghi e dalle leve del potere dello Stato. Entrambe le Costituzioni non riflettono la visione dei rivoluzionari ispirata ad un modello di Stato laico governato da figure non militari né religiose. In questo contributo si propone un’analisi dei rapporti di forza tra i diversi attori politici: l’esercito, i movimenti rivoluzionari, i partiti e gli intellettuali. Tutti coinvolti e responsabili in forme diverse del processo di manipolazione del concetto di “Stato laico” e di progressiva egemonia dell’esercito nella elaborazione di entrambe le Costituzioni e nell’opera di marginalizzazione dei gruppi attivisti che hanno promosso l’insurrezione del 25 gennaio di quattro anni fa.

This study highlights how the army marginalized the revolutionaries’ vision with regard to civil state during the formulation of both the 2012 and 2014 constitutions. To answer this question, the study deconstructs the notion of civil state. The paper replies on the content analysis of the political parties’ statements, the army’s policies and practices in the aftermath of January 25th revolution till the beginning of 2014.

Nation-state, as a civil supreme authority with regulatory institutions based on rational and legal principles, wasn’t present in the Egyptian political culture and practice.[1] Throughout Egypt’s modern history since the beginning of the 19th century and the declaration of the Republic in 1952, nation-state was evacuated from its civilian essence and formulated as an authoritarian mechanism of domination under the rule of the army. With the transition towards socialism as a state ideology in the 50s, the army controlled the different tools of production through the National Services Project in 1978 that was in charge of projects’ implementation in civil sectors under the army tutelage. The army ran almost from 25% to 40% of the Egyptian economy and dominated 10% to 30% of the national production by having a share in the real estate, industrial companies and other social services. This is in addition to its privileged access to subsidized services and energy sources.[2]

The state was adopted as a modern institutional framework but without its normative requirements. The rule of law, the regulatory mechanisms of power rotation and the presence of influential oppositional parties were quasi-absent in practice. This resulted in a gap between the state structure adopted by the army and the fulfillment of the state regulatory, distributive, symbolic and welfare provision role. The one party system dominated the political scene under Nasser regime (1954-1970) till the 70s during Al Sadat rule (1970-1981). It even existed with the introduction of “the tribunes” where the Egyptian Parliament was divided into three tribunes standing for the right, left and middle political currents that evolved to a multiparty system in the 90s.

Although divers political orientations and ideologies were tolerated through political parties under Mubarak regime (1981-2011), political participation and fair competitive elections weren’t in the political game. The upper hand remained to the National Democratic Party, as the sole grassroots ruling party whose leader, the president of the Republic, is the army Chief-of-Commander. The state ensured its legitimacy through the recourse to a religious rhetoric, with the support of Al Azhar and the Coptic Church. Only the Islamic groups, ranging from the Salafists to the MB managed to survive politically both as an organized but ineffective political opposition and a sociopolitical catalyst that filled in the state deficiencies in service provision in local deprived areas.

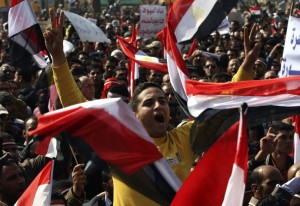

Calls for establishing a civil state increased after January 25th uprising, notably with regard to the end of the military rule in Egypt. The term “civil” rallied the Egyptian national figures and political forces facing the state repression and security domination. The uprising filled the public sphere with protestors from a wide array of sociopolitical movements including activists and ordinary citizens from different political orientations, sociocultural and professional backgrounds. They expressed a national unanimity in describing the civil state as an instance that guarantees freedom, social equity, human dignity and civil rights.

Civil state as defined in the revolutionaries’ slogans and chants was alienated from the intellectual and political debate around the 2012 and 2014 constitutions that was overwhelmed by the secular-Islamic division. This dichotomy was highlighted in diverse writings about the origins of the civil state debate in Egypt. On the one hand, it was estimated that this debate arose in the 50s after the military coup in Egypt. The Muslim Brotherhood (MB) reacted by initiating it sown conception of an Islamic state that has a civil elite in opposition to the rule of the army. Nasser’s wide campaign of arrest and torture against many of the MB’s members during the 50s and the 60s sparked the tension between them and the army. This was reflected in the former’s conception of civil state that should be mainly of a non-military nature. On the other hand, some referred to the European history of the civil state born in 1648 out of the separation of the state institutions from religions the main departure point of the debate.

The first context is underlined by the MB in their debate about civil state that revolves mainly around the nature of the ruling elite while insisting on the religious foundations of its laws and jurisdictions. The secular parties and intellectuals refer to the other one. They underline the European legacy in the definition of civil state. For them, it’s a ruling institutional body that should be away from any religious or military interference in its elite’s selection and legal premises. Being intimidated to express an explicit support for a secular nation-state since the 50s, the post-revolutionary context provided them an opportunity to present their vision. In light of the public opposition to secularism as a normative change to the cultural identity and the religious affiliation of the nation, secularists were always auto-defined as an alternative to the Islamic and military rule during the 2012 constitution marked by the army-Islamist consensus. However, different secular groups were content to present themselves as opponents to the Islamic rule only in order to avoid antagonizing the army during the 2014 constitution.

The State Discourse and the Revolutionaries’ Marginalization

The notion of civil state emerged during the January 25th revolution and figured on the protestors’ banners saying «a civil state, neither confessional nor under the rule of the army»; «a civil state, not theocratic or religious». The term civil state, accordingly, reflects the protestors’ call for a state that guarantees people’s sovereignty, freedom and rights independently from a religious or a military rule that have exclusive worldviews and manifest a discriminatory nature in the formulation and implementation of the state policies. However, the debate on state civility was marked by the secular-Islamic dichotomy during the formulation of the 2012 and 2014 Constitutions. The first constitution witnessed a military-Islamic consensus on the Islamic nature of the state and the preservation of the army’s prerogatives. However, the second one was dominated by figures from secular parties and others affiliated to the state establishment without the Islamists.

The 2012 Constitution and the Islamist-Army Consensus

After the MB victory in the legislative and presidential elections with 47.2% and 51.7% respectively, different secular parties started battling the political identity of the Egyptian state against both the Islamists and the army. During the formulation of the 2012 constitution, secular intellectuals like Gaber Asfour, Ashraf Azizi, Naoual El Saadawi, Naguib Sawiris and many others published an online statement under the following title “Towards a civil state” in March 2011.[3] It opposed religion interference into politics and state authority while calling for the separation between religion and state institutions, notably the legislative bodies. It consisted mainly of a clear position adopted towards the second article of the 1971 constitution stipulating that «Islam is the state religion and the Sharia principles constitute the main source of legislation». It called also for its abrogation and the restitution of the liberal version of 1923 constitution stipulating that all Egyptians are equal in their civic, political rights and responsibilities without discrimination on the basis of race, religion or ethnicity. The recourse to the Islamic jurisprudence in the regulation of the state affairs was rejected, as Islam, according to the statement, should remain a part of the nation’s social history without dominating the state identity. It contended that a state with an Islamic reference is the same as a theocratic state as the Free Egyptians Party leader, Sawiris, considered that the election of an MB member is an attempt for establishing a religious state.[4]

Among the politicians who supported this secular version of a civil state, figures a member of the Socialist Public Alliance, Abdel Ghaffar Shokr. He declared that there isn’t any suspicion about the emergence of a theocratic state in Egypt and contented that public pressure will obstruct any deviation. He added that the civility of the state should be protected by a legal declaration that has asupreme position and defines the constitution guiding principles like the French Declaration of Human Rights.[5]

On the other hand, Asfour considered that a civil state should possess a constitution based on positive laws and jurisdictions inspired of a “human reference”. The National Salvation Front expressed a similar position by indicating that the absence of religious authority is a sine qua non criterion of a civil state where authorities’ check and balance, equal citizenship, social equity and democracy prevail.[6] It perceived civil law as the main protector of freedoms and rights in a modern state in contrast with a restrictive religious law.

The Justice Party expressed the same position.[7] It called for a civil, free and modern state, in line with its liberal and social orientation, that respects the Egyptian traditions, bypasses ideological polarizations and empowers the state civil institutions within a religious coexistence. The Egyptian Social Democratic Party endorsed the same point of view. It emphasized its socio-liberal ideology by calling for wealth redistribution in favor of the workers within the market economy as the main role of a civil state. It also joined the Egyptian Liberal Party and the Assembly Party in a coalition called the “Egyptian block” to defend their call for establishing a civil state during the legislative elections in 2011 but gained only 34 seats.[8]

Another political and academic figure, Amr Hamzawi, emphasized the human references a basic criterion for a civil state jurisdiction [9]. He called for a civil state that is respectful of freedom and legal principles inspired of human thoughts and ideas. Establishing a civil state, accordingly, should go beyond the secular-Islamic dichotomy. More importance should be accorded to the supremacy of law as the sole exit from the debilitating conditions of the society in politics, public services, the economic dire situation and high unemployment rate reaching about 60%. This process requires a serious focus on state development instead of struggling the controversy of religion status in the formulation of the state constitution. Ayman Nour, the leader of Al Ghad Party, adopted the same point of view by emphasizing liberalism as the main pillar of a civil state towards the insurance of freedom and social equity.[10]

As for the state religious institution, Al Azharissued «Al Azhar and the Intellectuals’ Elite Statement about Egypt’s Future» stipulating that Egypt is a modern constitutional and democratic nation-state. It advocated for a state inspired by religion in its jurisdiction without emphasizing its Islamic character. Al Azhar represented the state official stance through a declared position based on societal and religious commonly agreed broad values. Its main argument revolved around the adoption of the Sharia principles as legal guidelines in state affairs while giving the priority to the former over the latter. Being in the same sensitive position towards the state, the Coptic Church avoided joining the occurring debate about civil state. It endorsed the centrality of religion in regulating the state affairs by calling for the reformulation of the second article of the 1971 constitution where the Sharia should be one of the sources of legislation instead of being the main source. This reformulation would allow other religious sects to refer to their own jurisdictions in organizing their personal affairs and religious practices.

The Egyptian Mufti indicated that politics would be regulated by a pluralist competition among political parties that shouldn’t alienate Copts by having religious programs or orientations. He supported the establishment of a civil state that doesn’t conflict with the Islamic legal foundations and presents a different adaptation of the term than the Western model of secularization.[11]

This argument asserts that the state is a political phenomenon that hasn’t been mentioned in the religious jurisprudence unlike the “Umma” but is a necessity for the latter’s sociological survival. It endorses the fact that the Islamic jurisprudence didn’t define a specific type of a state governance leaving it as a matter of discretion among nations and communities in light of their specificities. Islam only enumerates guiding principles for social organization that can be adapted to different forms of governance. There fore, the state has an Islamic character based on the reference of its legislation to the Islamic jurisprudence but not on the appointment of a theocratic “religious” government.

The seculars’ alerted position against Islamists doubled with the emergence of many Islamic parties after the revolution like “the Justice and Development”, “Al Nour”, “El Nahda”, “the Egyptian Current”, “the Development and Reform” and “Riyada”. It is worth noting that many of these parties, notably Al Nour and the Development and Reform, have explicitly rejected the notion of civil state as a Western innovation based on secular premises in governing state affairs. They asserted that a state should refer to the Islamic jurisdiction in its laws and regulations. Accordingly, rulers should render governance to God and base their authorities upon people’s choice for the fulfillment of its duties in accordance to the Sharia rules. Nevertheless, this position is a bit different from that of the MB. For them, a civil state is a democratic constitutional one based on the Islamic jurisprudence that organizes all aspects of life through general rules and principles that are a subject of interpretations for their legal appropriation and implementation.[12] As Islam doesn’t call for a theocratic state but a democratic one based on people’s will in the application of the Sharia’s rules, they recognize the civil state as a legitimate form of governance.

The MB tried not to antagonize any of the secular groups in the aftermath of the presidential elections. The Egyptian ex-president, Mohamed Morsi, underlined that his arrival to power as an elected president versus the SCAF is a success of the civil state [13]. He defined civil state as a democratic, constitutional and modern state ruled by elected deputies and representatives. Accordingly, the state ruling system should be based on equal citizenship, consultation, check and balance between authorities, the rule of law and the civility of the state rulers. Therefore, they implied an adapted form of an Islamic state by stating that it’s main character resides in the rulers’ civility, which excludes both the army and religious authorities, and that it is based on people’s will. They also had the advantage of aligning with the public aversion of secularism that is considered as a pervasive model of governance undermining the nation’s Islamic culture and identity. Accordingly, the MB indicated that civil state based on secular foundations as in Western countries can be selectively in spiring for the procedural mechanisms of democracy.

In their public declarations about civil state, the MB highlighted the comprehensiveness of Islam as a religion concerned with its adherents’ belief but not limited to a religious conviction or a set of worships. Its normative and legal foundations extend towards the organization of all matters of life including state affairs and politics. This perception of the civil state based on its main intellectuals’ ideas was adapted in compliance with the national exigencies. The MB capitalized on the similarity between their perception of how a civil state should be and the state’s vision. They indicated that the Islamic character of the state resides in its mission and legislation and not in its authority that should be maintained by civilians. According to this definition, any state with an Islamic reference abiding by democratic mechanisms for regulating state affairs is civil. This position rallied support from Al Wasat Party, a divergent group from the MB. It looked forward establishing a civil state with a religious reference where Sharia endorses freedom and rights as long as they are in conformity with its principles, according to Essam Soltan, the vice-president of the party.[14]

Although the 2012 constitution was prepared by an elected committee of 100 persons: half of them from the parliament on a proportional basis and the other half are representative of the other groups of the society, the Islamists’ victory discouraged seculars from joining the committee. It incited them to address the SCAF to reconsider the minorities’ selection mechanisms and criteria. Many figures among the liberals and the socialists boycotted the constitutional committee, leaving the Islamic parties as the dominant actors [15]. The 2012 constitution conceded a lot of competencies and prerogatives to the army while highlighting the Islamic character of the state and its legislative sources. For example, article 198 granted the army the right to sue civilians before military courts while article 50 and 51 conditioned the right to protest to the approval of the state officials and rendered civil organizations and NGOs a subject to state censorship based on judicial verdicts respectively. In addition, article 197 stipulated the creation of a Council for National Defense and Security charged of taking decisions regarding the state security affairs, the army budget and the bills related to the armed forces affairs. Moreover, article 219 defined the sources of the Islamic Sharia that is the main legal reference of the state legislation according to article 2 to which the government should refer in its policies and practices.[16]

The 2014 Constitution and the Secular-Army Consensus

The 2014 Constitution and the Secular-Army Consensus

Morsi’s demise in July 3rd 2013 gathered a wide support among the public and the different political parties including the Salafis who perceived the army’s intervention as a necessity to topple the MB rule. The army managed to rally a wide public support for deposing Morsi and ensuring its domination on the state affairs without competition. In light of this political turmoil breeding antagonism against the MB and any potential Islamic role in politics, the state, under the army’s authority, lessened the Islamic tone in the 2014 constitution without undermining the reference to Sharia in the state legal foundations. For example, during the constitutional committee debate in 2014, Mervat El Telawy, the head of the National Council of Human Rights, called for the abolition of article 219 from the constitution. It also endorsed the affirmation of the Constitutional Court role as the sole interpreter of the Sharia sources instead of Al Azhar and the elimination of the mention of «without violating the Sharia principles» in many articles as advocated by Mina Sabet, a member of the Egyptian Coalition for Minorities.[17]

Accordingly, the constitution confirmed the jurisprudence of the Copts and Jews as a source of legislation side by side to the Islamic Sharia in the organization of their personal and religious affairs. Only Sunni Islam, Christianity and Judaism were recognized as the official religions in Egypt whereas the other religious sects and groups like Bahais and Shia Muslims weren’t mentioned. It considered Al Azhar as an independent scientific instance in the organization of its own affairs that acts as the main reference in the interpretation of the religious sciences and the regulation of the Islamic affairs. Besides, article 44 criminalizing offensive practices against Prophets and the additional paragraph concerning «the consultation of Al Azhar scholars in matters related to Sharia» were both abrogated.[18]

The constitution of 2014 adopted a conciliatory stance towards Al Nour Salafist Party, the leftist and the nationalist-conservative trends in the definition of the civil nature of the state. It limited the state civil character to the non-religious affiliation of the elite, hence eliminating its rival, the MB, while asserting the important role of the Sharia in the state legislation. Al Nour party, being the main competitor of the MB with whom it was on bad terms in light of its marginalization in the repartition of ministerial portfolios in 2012, was coopted by the army. It supported the army in demising Morsi or accepting the state definition of civility in the 2014 constitution in spite of its refutation by many of the Salafist scholars. Besides, it presented also a source of religious legitimization for the army along side the Church and many other secular parties before the public against the MB.

As a result, the notion of “civil” was added to the preambule stipulating «the creation of a modern democratic state with a civil government» while the mention of its liberal and inclusive character was limited to the committee discussions only. This maneuver helped the state to keep a conciliatory definition of a civil state among the secular trends and the Salafists in the committee and ensure the ruling regime’s interests. Its partial definition of civility restricted to the rejection of the religious character of the rulers eliminated the MB threat and preserved the Sharia as a main source of legislation deemed necessary for the legitimization of the regime’s non-democratic tenure. Hussein Abdel Razik, a member of the committee and the ex-president of the Assembly Party, confirmed this duality.[19] His vision of the civil state was based on the full principle of citizenship, citizens’ freedom and equality without distinction in duties and responsibilities under the auspices of a civil and a “positivist” constitution preserving the state’s affairs from any religious or military interference. However, this perception wasn’t reflected in the constitution that accorded more concessions to the army.

The non-Islamist members of the constitutional committee were mainly determined to restrict any mention of religious reference in the constitution while keeping the same prerogatives attributed to the army in the 2012 constitution.[20] The head of the committee, Mona Zullfukar, refused any kind of state activities based on religion in light of the intellectuals’ statement calling for the condemnation of any political activity based on religion or ethnicity. They added more restrictions to the parties with religious background that can only survive by abiding by the state’s vision of civility and showing tolerance towards other religions.

In this regard, the regime, based on its concern of confirming the civil character of the state, enacted a set of laws obliging citizens to respect the national anathem of the state. Moreover, it imposed the inclusion of 3 to 9 Copts at least in the parties’ electoral lists as a threshold for participating in the legislative elections. Being a staunch supporter of the army in its takeover of power and a member of the constitutional committee, Al Nour Party, faced a dilemma. As its vision about the state reflected in article 219 of the 2012 constitution doesn’t meet with the army’s stance supported by the other secular parties, it had to accept this new situation and conciliate between its political orientations and the new enacted laws in order to guarantee its political survival.

Conclusion

In the aftermath of January 25th revolution, the revolutionaries’ slogans underlined a basic component about the notion of civil state. For them, it is a form of organization where individuals are not submissive to primitive allegiances or to any other form of domination under the army or a theocratic instance. It is rather a state based on equality and justice without discrimination among its people in reference to religion, language, race, ethnicity or color. However, in both 2012 and 2014 constitutions, the fear of a dominating theocracy and the insurance of the army’s dominant role were the main obstacles behind the inability to establish a civil state as advocated by the revolutionaries. Instead of displaying a clear-cut political position expressing an ideological orientation, they emphasized the importance of the nature of the ruling authority. Accordingly, this authority has to be civil which means that it mustn’t be reflected through a military or a religious candidate as was the case during Mubarak and the MB eras.

A distorted vision of civility dominated politicians’ views, notably the seculars who for the sake of political survival and out of fear of an Islamic takeover of power accepted the army’s empowered position although civility implies not only a non-religious government but a non-military one as well. As a result, after Morsi’s eviction and the escalation of the public anger against the MB, many denied the contradiction between the civil character of the state and the ascension of a military figure to power. Thus, the civil character of the state isn’t undermined by the ascension of a candidate with a military background to presidency or the army’s penetration into the state affairs. Its acquisition of an exceptional positionen dorsed by constitutional provisions in addition to the ownership of means of production and economic institutions as well as impunity from repressive and anti-humanitarian practices would be tolerated.

The civil state debate maintained the secular-Islamic dichotomy as mutual misperception persisted between both sides who were confined in a zero sum political game. The bargain for the rejection or the inclusion of the Islamic reference was a mutually exclusive tactic for harming the political rival. The different political parties manipulated the notion of “civil state” as they usurped its premises to stigmatize opponents and rally more supporters after January 25th. The presence of a permanent contention between both the Islamic and secular parties about the nature of the civil state, favored the army’s position in the formulation of both constitutions, notably in 2014, where it succeeded to gain a public consensus over the limitation of the Islamists’ power while preserving the nation’s religious identity and values through the second article of the constitution.

Dialoghi Mediterranei, n.16, novembre 2015

(*) Per espressa volontà dell’Autrice si pubblica in lingua originale

Note

[1] Braud, Phillipe, 2002, Sociologie politique, 6th edition, Paris: L.G.D.J.: 117-168.

[2] AbdelHadi, Magdi, 2014, “Egypt’s Army in Control of a Vast Business Empire”, BBC Arabic, june 23. Accessed on december 11, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-18548659

[3] http://www.dawlamadaneya.com/ar/index.php/2011-03-10-13-54-17.

[4] Abdel Mohsen, Somaia, 2014, “The Civil State, Between the Exclusion of Religion and the Ignorance of Militarization”, The Center of Civilization for Political Studies, march 4, 2014: 5.

[5] “Egypt’s Future After January 25 Revolution Between the Civil and the religious State”, june 29, 2011. Accessed on december 10, 2014, http://arabic.people.com.cn/31662/7424191.html

[6] Abdel Mohsen, 2014: 2.

[7] “The Justice Party Holds its First Conference at Azhar Park”, october 30, 2011. Accessed on december 20, 2014, http://www.masress.com/shorouk/449102

[8] Salem, Mohamed, 2014, Al Shorouk Newspaper. january 22, 2012. Accessed on december 15, 2014, http://www.shorouknews.com/news/view.aspx?cdate=20012012&id=d2197e3d-8ea8-4bad-a70c-1a0ecd706bf5

[9] Hamzawy, Amr, 2011, “About The Necessity of a Civil State”, Al Shorouk Newspaper. october 18, 2011. Accessed on december 10th, 2014, http://www.shorouknews.com/columns/view.aspx?cdate=18102011&id=3f6a0218-cf62-4dbd-aade-fdbd0efd9e0a

[10] “Ayman Nour Presents His New Party Papers Before the Party Affairs Committee”, Al Youm Al Sabea. august 17, 2011. Accessed on december 10, 2014, http://www.youm7.com/story/

[11] Dr. Ali Gomaa, the state Mufti: The Civil State is the one that complies with the Sharia, Islam doesn’t recognize the theocratic state, april 29, 2011. Accessed on july 21, 2015, http://www.youm7.com/story/2011/4/29/الدكتور-على-جمعة-مفتى-الجمهورية–الدولة-المدنية-هى-التى-تتوا/400443#.VbGN50vdLwI

[12] The MB Justice and Development Party program, http://www.hurryh.com/Party_Program.aspx, in case of source restriction please consult Khouri et al., 2013.

[13] Mohamed Morsi’s speech after his press conference with chancellor Angela Merkel, january 30, 2013. Accessed on december 10, 2014, http://albedaiah.com/node/18142

[14] Al Wasat Party’s Conference in Alexandria, june 3, 2011. Accessed on december 12, 2014, https://hazemhassanin25.wordpress.com/2011/

[15] Withdrawals from the Constitutional Committee May Lead to a Crisis in Egypt, Archive.arabic.cnn. november 22, 2012. Accessed on july 20, 2015. http://archive.arabic.cnn.com/2012/middle_east/11/21/Egypt-Constitution/

[16] The Egyptian constitution, 2012. Accessed december 25,2014, http://www.sis.gov.eg/newvr/theconistitution.pdf

[17] Abdel Mohsen, 2014: 5-8.

[18] Bernard- Maugiron, Nathalie, 2014, La constitution egyptienne est-elle revolutionnaire? La revue des droits de l’homme, 6: 2-24.

[19] Abdel Mohsen, 2014: 5.

[20] The Egyptian Constitution, 2014. Accessed on december 20, 2014, http://www.sis.gov.eg/Newvr/Dustor-en001.pdf

_______________________________________________________________

Shaimaa Magued, docente presso la Facoltà di Economia e Scienze politiche nell’Università del Cairo. Attualmente sta insegnando a Humphre nella Scuola di affari globali dell’Università del Minnesota per il semestre autunnale del 2015. Ha conseguito un Dottorato nell’Institut d’etudes politiques d’Aix in Scienze politiche e relazioni internazionali nel 2012 e un Master in Politiche pubbliche presso l’Università americana del Cairo (AUC). I suoi interessi di ricerca e le sue pubblicazioni sono principalmente focalizzati sul Medio Oriente e sulle strategie politiche dei diversi Paesi nonché sull’Islam politico con particolare attenzione per la Turchia moderna e le relazioni turco-arabe.

________________________________________________________________