di Roberta Marin [*]

In the Tunisian art scene between the 20th and 21st centuries there is an artist who stands out among the others and that is Safia Farhat (née Foudhaïli). She made a name for herself not only thanks to her eclecticism in art and her inclination to experiment with all sorts of different materials and techniques, but also for her role as an advocate for human rights, particularly those of women, and as an educator. (Qassemi, ‘Modern Arab art and the depiction of blue collar workers’, 2016). Born into an elite family in 1924 in Radès, a port city about 9 km away from the capital Tunis, Farhat could attend the primary and secondary schools of the French Protectorate and was one of the few students to graduate from the colonial Tunis Institute of Fine Arts (Gerschultz, ‘Farhat, Safia (1924–2004)’, 2016a). She is considered a pioneer of modern art in Tunisia and was the only female member of the famous École de Tunis (the Tunisian School), an art movement founded in 1948 which had the clear aim of breaking with the Orientalist trend of the time and the need of creating a truly Tunisian pictorial style. Other famous members of the same group were Yahia Turki (1903-1969), Ammar Farhat (1911-1987) and Abdelaziz Gorgi (1928-2008), just to mention a few.

Few years after the independence of Tunisia from the French and the promulgation of the progressive Code of Personal Status (CPS), which promoted the equality between women and men in many areas of the Tunisian society (Benanzato, ‘Biennale arte, Safia Farhat: tutti i colori della Tunisia’, 2022), Farhat co-founded with the journalist, art critic and feminist Dorra Bouzid the women’s magazine Faïza, Revue Feminine Tunisienne, which ceased to be published only in the late 1960s after 62 issues. Faïza is still today remembered as the first and perhaps most famous Arab-African feminine francophone magazine (Talass, ‘Trailblazers: Safia Farhat – Tunisian artist, educator and activist now gaining global renown’, 2023). The artist was also behind the creation of the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women and at about the same time she started teaching at the School of Fine Arts in Tunis, where she was in charge of the atelier of decoration. In 1966 she was appointed director of the School, position that held till 1973. In her capacity as a teacher and, later, as a director, she put a lot of effort in reorganising the school curriculum and enabling students to learn not only the so-called fine arts, especially European painting, but also traditional arts and crafts, so important in Tunisia and throughout North Africa (Micaud 1968: 79). Under her supervision the School of Fine Arts was annexed to the national university system and became known as the Institut Technologique d’Art d’Architecture et d’Urbanisme de Tunis (ITAAUT). Farhat was the president of the Association des Peintres et Amateurs d’Art en Tunisie and together with her husband, the socialist politician Abdallah Farhat (1914-85), she founded the Centre des Arts Vivants (Living Arts Centre) in Radès, her hometown, which was donated to the country in 1981. The centre is still very active today and it promotes all sorts of artistic creation. It is organized into a number of separated spaces, each dedicated to different art forms, such as ceramic, engraving, weaving, and sculpture, but there also a dance hall, a photographic laboratory, individual studios for artists in residence and a library. Part of the centre has become the Safia Farhat Museum, which was inaugurated by the artist Aïcha Filali, Farhat’s niece, in 2016.

Over the years Farhat has constantly tried to enhance Tunisian and consequently North African artistic traditions, paying great attention to craftsmanship. By doing so, she wanted to expose the true essence of Tunisia and allow the work of the artists to be recognize at international level. At the beginning of her career, Farhat focused on painting and portrayed local women and men dressed in the traditional way and accompanied by indigenous plants and animals of the region and everyday objects. The canvases overflow with colour and although the forms are rather sparse, almost simplified, the message that the artist wants to convey is clear ad articulated: she aims to place Tunisian society in all its facets at the centre of her practice (Hancock, ‘Safia Farhat’, 2018).

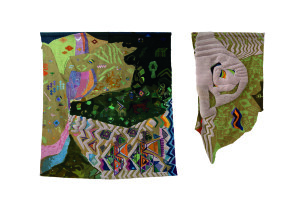

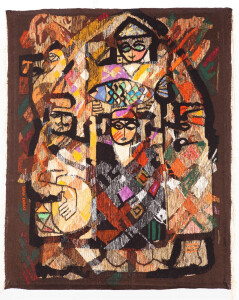

Fahrat had fruitful collaborations with important artists, such as Abdelaziz Gorgi, who was also her colleague at the Tunis Institute of Fine Arts. Both artists were very keen in giving new impulse and consideration to the artistic heritage and local crafts and successfully established a link between art schools and the public and private sector. With the common intention of reviving the purely Tunisian decorative art, they founded a design company, the Société Zin, in which numerous craftsmen from the most disparate areas of specialization were employed. Together with a group of skilled weavers, for example, Farhat produced large-scale tapestries, decorated in some cases with realistic scenes of daily life and in others with a more imaginative, almost surrealist approach. There are also some tapestries which evoke mythological legends, such as that of Ulysses and Penelope, or the epic of the confederation of tribes known as Banu Hilal, who migrated from the Arabian Peninsula in the 11th century initially to Egypt and then to North Africa. Farhat is considered a pioneer of the genre in Tunisia and because of that she was celebrated at the Biennale d’Arte in Venice in 2022 with the display of her diptych Gafsa & ailleurs (Gafsa & elsewhere), made in 1983. The two-part tapestry is large in size and presents a collage-like structure with three-dimensional effects, achieved by using different pile thicknesses, heights and textures. The colourful and lively scene shows on the one side a horse galloping on the field between tall hills and on the other, what resembles a cluster of buildings with human beings, engaged in some sort of activities. The scene could be a faithful representation of the mountain oasis of Gafsa, but as the title suggests, it could be any other place in Tunisia or in the world, as much as a place of the soul. The artist represents a bucolic, verdant landscape where animals, human beings and nature live in a utopian harmony (Weisburg, ‘Safia Farhat’, 2022). By looking at the tapestry, the viewer would have the impression that the scene is not framed but continue beyond the borders of the textile in what resembles an ideal world. The technique adopted by Farhat was inspired by the traditional weaving craft of the women of southern Tunisia and most probably she employed the skilful weavers of Gafsa itself. The use of dyed, hand-spun wool was a tribute to these women and their weaving expertise and more generally to the old, sometimes ancient, Tunisian craft techniques.

Mère et enfants (mother and child), c.1970, tapestry, Barjeel Art Collection, Sharjah, source: arabnews.com

Farhat is also considered part of the New Tapestry (or Nouvelle Tapisserie, a term coined by the Swiss critic André Kuenzi in 1973), a sort of trans-national movement in which artists were engaged in investigating the possibility of using fibres to create free standing, three-dimensional conceptual works of art. They would question the way in which tapestry and more generally weaving, macramé and crocheting had been used until then (Gerschultz 2016b: 5).

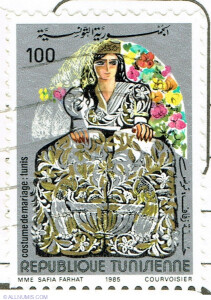

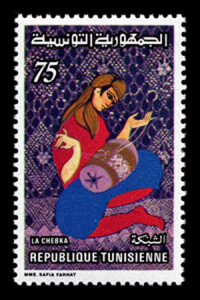

In other tapestries, held today at the Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah, the artist portrays two important moments in the life of a woman, such as the marriage and the maternity. In these artworks, the women are dressed in a traditional way and great attention is paid to details. The patterns of the fabrics and the style of the headdresses are carefully replicate.

The portrayed figures have a monumental aspect, inspired by sculpture. Scenes with similar monumental figures were designed for sets of national stamps, some dedicated to traditional clothes, as seen before in the Barjeel tapestries, but also to traditional architecture and local craft (Chebka lace). Farhat used the same artistic repertoire, drawn from Tunisian cultural heritage and local craftsmanship mixed with modernist art, to produce large murals. Some of them are still in place and decorate government buildings, hotels, banks and schools, such as the Central Bank, the National Tourism Office and the Tunisian Sugar Company. These lively and elegant murals were made using a selection of materials: ceramic tiles, paint, stone, iron and wool (Gerschultz, ‘Safia Farhat’s hybrid creatures in civic spaces’, 2022).

Depending on the places where the murals were to be exhibited, the artist chose to portray human beings engaged in working activities, such as laborers and craftsmen, or fantastical figures surrounded by flowers and birds and various elements taken from the natural context. Geometric, abstract and stylized forms and shapes, typical of both her artistic repertoire and Tunisian craftsmanship, found their place there as well. In the ceramic tile mural created for the reception hall of the Hôtel Skanès Palace in Monastir-Skanès, the main character is represented by a naked woman with large almond-shaped eyes and long hair blowing in the wind and fixed by a diadem on the forehead. The creature seems to emerge from the sea and the whole scene is enriched by a series of highly stylized flowers, plants and other elements, probably symbolic. In the panels superimposed on the composition are respectively a pair of gazelles and a geometric, almost totemic representation of a living being, be it a tree, an animal, a human being or a blend of them.

Mural with sea creature, c.1963, ceramic tiles, Hôtel Skanès Palace, Monastir-Skanès, ph: Jessica Gerschultz, source: post.moma.org

In the interior of the Tunisian Sugar Company in Béja, however, the artist has created a more realistic mural, which shows some workers holding their tools and ready for what could be their work shift. They are portrayed as men with a strong, robust physique and well-defined facial features. In the distance there is a cluster of buildings, perhaps a stylized representation of their factory.

The versatility in art and the strong political and educational commitment of a woman and an artist like Safia Farhat cannot be easily summed up in a few words. Her artistic practice was steeped in politics and perfectly reflected her vision of a modern Tunisia, which struggled to reveal its identity, its true ‘Tunisianess’ after the years of French colonization, but was able to rediscover it, at least in part, in its millenary history and revival of art and craftsmanship. Safia Farhat has forged new generations of artists and women and her legacy cannot be belittled or overlooked.

Dialoghi Mediterranei, n. 63, Settembre 2023

[*] Abstract

La scena artistica tunisina del Novecento è stata caratterizzata da grandi artisti, che hanno raggiunto una certa fama sia entro i confini nazionali che all’estero. Nel corso degli anni però, alcuni di loro sono stati un po’ ‘trascurati’ dai mercanti d’arte e dai collezionisti, e questo è il caso di Safia Farhat (1924-2004). Nel 2022 la sua figura di artista versatile e politicamente impegnata è tornata alla ribalta con grande enfasi e a livello internazionale grazie a Cecilia Alemani, la curatrice della 59esima Biennale d’Arte di Venezia, che ha voluto includere tra le opere in esposizione il suo arazzo ‘Gafsa e altrove’ del 1983. In quest’opera è evidente la maestria di Farhat nel rappresentare uno scorcio della Tunisia e il suo desiderio di utilizzare e celebrare le tecniche di tessitura tipiche della zona meridionale del Paese. Safia Farhat non solo ha dimostrato di essere un’artista poliedrica, ma è stata anche una donna che si è battuta per tutta la vita e in prima persona per modernizzare la Tunisia, e per far sì che le donne avessero gli stessi diritti degli uomini sia nella professione che in famiglia.

Riferimenti bibliografici

A. Benanzato, ‘Biennale arte, Safia Farhat: tutti i colori della Tunisia’, Askanews, April, 20, 2022, https://askanews.it/old/op.php?file=/cultura/2022/04/20/biennale-arte-safia-farhat-tutti-i-colori-della-tunisia-pn_20220420_00028, (accessed August 9, 2023).

J. Gerschultz, ‘Safia Farhat’s hybrid creatures in civic spaces’, Post notes on art in a global context, MOMA, Museum of Modern Art, New York, January 26, 2022 https://post.moma.org/safia-farhats-hybrid-creatures-in-civic-spaces/ (accessed August 7, 2023).

-. ‘Farhat, Safia (1924–2004)’, The Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism, 2016a https://www.rem.routledge.com/articles/farhat-safia-1924-2004 (accessed August 8, 2023).

-. ‘Mutable Form and Materiality: Toward a Critical History of New Tapestry Networks’, ARTMargins, vol.5, no.1, 2016b: 3–29.

C. Hancok, ‘Safia Farhat’, AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018 https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/safia-farhat/ (accessed August 6, 2023).

E. Micaud, ‘Trois Decades D’art Tunisien’, African Arts, vol.1, no.3, Spring, 1968: 46-55 and 78-84.

S. S. Al Qassemi, ‘Modern Arab art and the depiction of blue collar workers’, Qantara, 2016 https://en.qantara.de/node/41795 (accessed August 9, 2023).

R. Talass, ‘Trailblazers: Safia Farhat – Tunisian artist, educator and activist now gaining global renown’, Arab News, April 3, 2023 (accessed August 5, 2023).

M. Weisburg, ‘Safia Farhat’, La Biennale di Venezia, 2022 https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/milk-dreams/safia-farhat (accessed August 7, 2023).

L. Yakoub, ‘Abdelaziz Gorgi, Tunisia (1928 – 2008)’, in Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut, n.d., https://dafbeirut.org/en/abdelaziz-gorgi (accessed August 10, 2023)

__________________________________________________________________________________

Roberta Marin ha conseguito la laurea in Lettere Moderne con indirizzo storico-artistico all’Università di Trieste e ha completato il suo corso di studi con un Master in Arte Islamica e Archeologia presso la School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) dell’Università di Londra. Ha viaggiato a lungo nell’area mediterranea e il suo campo di interesse comprende l’arte e l’architettura mamelucca, la storia dei tappeti orientali e l’arte moderna e contemporanea del mondo arabo e dell’Iran. Collabora con la Khalili Collection of Islamic Art e insegna arte e architettura islamica in istituzioni pubbliche e private nel Regno Unito e in Italia.

______________________________________________________________