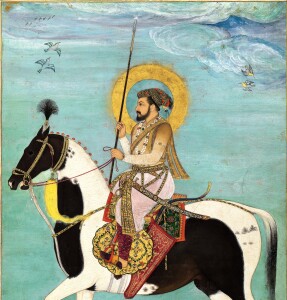

Shah Jahan on horseback, Mughal Empire, 16th-17th century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 55.121.10.21)

di Roberta Marin [*]

In the Islamic world, jewellery has been consistently produced and worn by both women and men. The most precious materials have been used, such as gold and silver, and the most expensive and sought-after gemstones have often been added to jewels to make them more colourful and above all luxurious. There are still beautiful examples of jewellery made by Muslim goldsmiths in private collections and public institutions around the world, but tracing the history of jewellery from Islamic lands is not an easy task for a variety of reasons. First, over the centuries gold and silver objects have been melted down to produce new pieces of jewellery and coins.

Secondly, unlike other works of art produced by Muslim artists and craftsmen, jewellery rarely bore the name of the craftsmen and the place and date of production. An exception is represented by the seal stones set on rings, which would bear inscriptions with a set of useful information, but the functions of seal stones or seal rings are totally different from those of the more precious jewels. Because of these two significant limitations in the history of jewellery production in the Islamic world, there are still today gaps that are unlikely to be filled in the short term, unless there is the unveiling of new important hoards or some jewels, held so far in a private collection, would suddenly appear on the art market.

Islamic jewellery was mainly produced using gold and silver, which according to the famous historian Ibn Khaldun in his Muqaddima (Prolegomena) were almost exclusively exported from Nubia (modern day Sudan) to the rest of the Islamic world (Dunlop 1957: 29). Precious and semi-precious stones were also lavishly added to jewellery. They represented a status symbol and an investment, but were also used for their talismanic and protective value. Arab scientists have extensively studied gemology and mineralogy and in doing so, not only they broadened the knowledge of gemstones and minerals’s properties, but also improved the mining techniques to extract them. Very rarely was the sale of gemstones recorded in trade records, only those of low value were mentioned. The reason was that the specialists involved in the gemstones trade dealt with potential customers in person, without intermediaries.

Sometimes the clients were very important political figures, such as, for example, the emperors and upper-class members of the Mughal empire, who liked to accumulate large quantities of precious stones in the palace treasury and bought, or refused to buy, the gemstones in person. Agates and carnelians were often used in the Islamic world, especially as seal stones. They had the intrinsic power to ward off evil, bad luck and disease and according to tradition, a silver ring with a carnelian was also worn by the Prophet Muhammad. Turquoises would prevent the owner from becoming poor. Rubies were considered the most valuable of all gems and linked to the myth of Adam. Emeralds were highly sought after as the shades of green typical of these gemstones would symbolise Islam, being green, according to tradition, the favourite colour of the Prophet Muhammad. Pearls and corals were also used to enrich jewellery pieces and there are evidences that the pearl trade dates back to around 8000 years ago. Above all pearls have become the favourite subjects of myths and stories in the Arabian Peninsula and in the Persian Gulf where for a very long time they represented one of the main sources of income.

A wide range of techniques have been employed in jewellery making, but none of them were invented by Muslims. They have been acquired from different traditions, the most popular of which descended directly from the Sasanians, the ancient Greeks, the Romans and the Byzantines, and continue to be in vogue today. The repoussé technique allows goldsmiths to create a raised or high relief design on the front of a metal object by punching the reverse side of the piece. The chasing technique is used alone or in combination with the repoussé. In this technique, the surface of the object is hammered on the front side, sinking the metal and forming the patterns. Full or partial gilding referred to the application of thin sheet of gold (or other metals) to the surface of an object, which would give a gold look to a piece of jewellery without the need to use more expensive solid gold. Fine jewellery is often decorated with plain or twisted wire filigree. Tiny beads or twisted threads are soldered to the surface of a piece of jewellery and arranged to create elegant, sophisticated patterns. Granulation can be paired with filigree and involves applying and soldering small spheres of gold or silver along the edges of the design motifs.

Niello and enamel are also often used to decorate jewellery. They are both fused to metal objects, but there are some key differences. Niello is metallic, while enamel is vitreous. Furthermore, niello is only available in various shades of black, the enamel in many colours. In both cases, however, the goldsmiths create an indentation or a depression or an engraved area on the surface of metal objects, which are filled with niello or enamel, then fused to the surface by heating. Niello is most often used to decorate silver pieces, as the contrast between the silver and black niello make the juxtaposition of colours more apparent. As far as enamels are concerned, however, there are two different techniques associated with enamels in jewelry: one is the champlevé technique and the other is the cloisonné technique. In the former case, cells are carved or cast into the surface of a piece of jewellery, then filled with enamels, which would then be fused. Once the object has cooled, the surface is polished. In the latter, the enamels fill the compartments, created on the surface of the piece by soldering or applying thin strips or threads of silver or gold foil, which would still remain evident after the fusing of the enamels.

The Basse-taille (French, ‘low cut’) and the painted enamel techniques were also sometimes used. In the case of the Basse-taille technique, goldsmiths create a bas-relief motif in gold or silver by engraving or chasing the object. The enamel is then applied and the light would contribute to an overall translucent effect by playing with the different thicknesses of the carving. Unlike the other techniques discussed so far, the one known as the painted enamel technique was developed in the late 15th century in Limoges in France. The process of decorating a jewel with this technique is long and requires highly skilled goldsmiths. The slightly convex surface of an object has to be prepared with a uniform colour, which would be the base of the drawing. Using a paintbrush, thin layers of enamel paste are applied at different times and between each application, the enamel must be fired to fix it. The end result would be very similar to that of oil paint on canvas.

We have no evidence that these techniques were employed by the early Islamic dynasties, such as the Umayyads (661-750) and the Abbasids (750-1258), as most of the jewellery made during their caliphates are irretrievably disappeared. Due to these limitations, the gold and silver pieces that have survived cannot be fully attributed to them, as they may have been made by the Sasanians or the Byzantines, the former ruling Persia until the rise to power of the Islamic caliphate, the latter were still strong when Umayyads and Abbasids held the reins of power in the Islamic world. The information we have about shapes and sizes of gold and silver jewellery produced in the time of the Umayyads and Abbasids comes to us thanks to the surviving frescoes fragments in the so-called Castles in the Desert, scattered in Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine – an example would be the pieces of jewellery worn by the figures in the wall paintings of Qusayr ‘Amra in Jordan, early 8th century – and in the Palace of Al-Mutasim at Samarra (833-42) (Khalili 2008: 133).

A large number of pieces of jewellery survived from the early medieval Islamic period and particularly from the 11th-century onwards in Iran and Egypt (Jenkins and Keene 1983: 39). The Great Seljuks (1037-1153) and the Fatimids (909-1171) were respectively in power in those areas and the technical and decorative ties between them are evident. Considering the Seljuk Empire first (Yalman 2001, based on original work by Linda Komaroff, ‘The Art of the Seljuqs of Iran (ca. 1040–1157)’, it can safely be said that the goldsmiths were commissioned with remarkable pieces of jewellery, such as the gold armlet decorated with filigree and granulation and the twisted shank, probably derived from Greek bracelets. The four hemispheres flanking the clasp were enriched with precious stones which are now missing. Another superb example of jewellery from Iran is a gold ring produced between the 12th and 13th century. It formed by a polygonal bezel, decorated with a geometric pattern in openwork filigree and granulation, and a cast shank enriched by anthropomorphic figures and harpies. These human-headed birds were believed to have some sort of protective and magical powers and became part of Iranian and Central Asian lore from the 11th century. The Fatimid caliphs ruled over an empire that stretched from North Africa to the Levant and the Hijaz. Nubia (modern day Sudan) was also under the control of the Fatimids, who took great advantage of the rich gold mines scattered across the country and enabled them to commission some of the most opulent jewellery ever produced in the Islamic world. The pieces were mostly made using the box construction, which allowed the objects to be decorated on both sides with plain or twisted wire filigree and granulation. Around the perimeter of earrings, pendants and armlets there are often small outward projecting wire loops, which held strings of pearls and precious or semi-precious stones. This typical element of Fatimid jewellery can be safely associated with Byzantine jewellery as well as the cloisonné enamel technique, which was used to decorate pieces of jewellery, mostly with single and confronted birds (Stewart, ‘Fatimid Jewelry’, 2018). A perfect example of the typical features of Fatimid jewellery can be found on a crescent-shaped pendant, produced in Cairo in the 11th century.

Crescent-shaped pendant with confronted birds, Egypt, 11th century, 30.95.37 (Metropolitan Museum NY)

In the late Islamic medieval period, jewellery is well represented by the extant pieces produced by the Nasrid dynasty (1230-1492) in Spain (Department of Islamic Art, ‘The Art of the Nasrid Period (1232–1492)’, 2002). They adopted the same techniques and types of decoration that we have already encountered in Fatimid jewellery and that can be easily identified in the elements of a gold necklace, made in Granada in the 15th -16th century and today held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Jenkins 1988: 41). Filigree, granulation, cloisonnè enamel (Rosser-Owen 2010: 72) loops along the perimeter and box construction are still very much in use, even if the necklace produced by Nasrid goldsmiths has not reached the refinement and complexity of the Fatimid pieces.

In the late Islamic period, the Ottomans (1299-1922) and the Mughals (1526-1858) manifested all their wealth by enriching gold and silver jewellery and everyday objects with an extraordinary large number of gemstones. If the Ottomans mainly added them to jugs, flasks, weapons (Rogers 2000: 154-167), belts and turban elements (Bağcı and Tanındı 2005: 263 and 328-29), the Mughals also ordered goldsmiths to produce superb pieces of jewellery, encrusted with the most expensive and sought-after gemstones. The jade bracelet with makara heads made between the 18th and 19th century is embellished by the addition of gold, enamel and semi-precious stone inlays. The makara was a mythical and legendary sea monster, used since ancient times in India to decorate temples and everyday objects. It is a composite animal, which included the head and the body of a crocodile, fish scales and tail, and sometimes elephant tusks as well. Mughals loved to wear jewellery and in this they were facilitated by the presence of rich mines of precious stones in the Indian subcontinent. As mentioned in the first part of this essay, Mughal emperors and members of high society dealt in person with specialists in acquiring gemstones and in doing so, they became true connoisseurs. The most famous was probably Shah Jahan (1592-1666), who was also the patron of the famous Taj Mahal complex in Agra. Emperors sometimes had their names engraved on precious stones, particularly remarkable for their fine quality or size. Sadly, most of the opulent jewellery produced by the Mughals in the first two centuries of their rule together with the most precious stones have been lost. We are aware of the fine patterns and motifs on the pieces and how they were worn by men and women thanks to paintings and contemporary accounts (Topsfield 2012:56-57 and 96-97). A greater number of jewels produced in the last two centuries of the Mughal empire survived and sometimes they were acquired by the British.

Crescent-shaped pendant with confronted birds, Egypt, 11th century, 30.95.37 (Metropolitan Museum NY)

An interesting chapter in the history of Islamic jewellery is occupied by that produced by Turkmen tribes in the 19th and 20th century. Pieces of jewellery were made primarily for women to highlight the different stages in life (age, marital status, offspring, etc.). Some pieces were worn on daily basis, even though the most spectacular parure played a fundamental role in the wedding ceremonies and included headgears, headbands, pendants, earrings, pectoral and dorsal ornaments, amulet holders, appliqués for silk garments, armbands and rings. Men also wore jewellery, but limited to daggers, belts and seal rings. The jewels were mostly made of high-quality silver and enriched by gilded elements and semi-precious stones, such as carnelians, agates and turquoises, used for their protective and talismanic properties (Diba 2011: 24).

Amulet case, one of a pair, present-day Uzbekistan, 19th century, 91.1.1145 (Metropolitan Museum NY)

The craftsmanship is not as sophisticated as it was in the jewellery made by previous Islamic dynasties, but the complexity of the motifs makes up for it. The motifs combined geometric and vegetal patterns, sometimes together with zoomorphic imagery (Department of Islamic Art 2011, ‘Turkmen Jewelry’). The pair of amulet holders from the Metropolitan Museum of Art would be pinned on each side of the bride’s chest on her wedding day. The central part is occupied by a cylindrical bozbend (tube), which contains a Muslim prayer scroll with talismanic and protective functions for the wearer (Al-Saleh, ‘Amulets and Talismans from the Islamic World’, 2010). The amulet holder would be completed by a series of drop-like hanging elements.

Silver and gold, precious and semi-precious stones, niello and enamels are just some of the materials used by goldsmiths to create the most elegant and opulent pieces of jewellery in the Islamic world. Sadly, not all the different stages in the history of jewellery have been well documented and it is very likely that they will never be, due to the widespread habit of melting down existing pieces of jewellery to produce new ones. What we already know, however, will help fuel our interest in Islamic jewellery and ignite our curiosity to find out more.

Dialoghi Mediterranei, n. 61, Maggio 2023

Abstract

La produzione orafa nel mondo islamico seppur affascinante, presenta ancora oggi delle lacune. Questa carenza di informazioni è da ricollegare all’abitudine delle dinastie musulmane, e non solo, di fondere gli oggetti d’oro e d’argento per la produzione di nuovi gioielli, più al passo con la moda del tempo, e di monete, con l’effigie dell’ultimo regnante al potere. Per colmare le lacune del primo periodo islamico, compreso approssimativamente tra il settimo e il nono secolo, ci vengono fornite utili informazioni dai frammenti di affreschi parietali ancora oggi visibili in alcuni Castelli del Deserto, eretti dai califfi Umayyadi in Medio Oriente. Per comprendere invece quali fossero le fogge dei gioielli e le tecniche impiegate nel tardo periodo islamico, rappresentato dai Safavidi di Persia e dai Timuridi dell’Asia Centrale, un contributo insostituibile ci viene dato dalle ricche miniature presenti nei manoscritti, in cui i regnanti, circondati dalla corte, vengono ritratti mentre indossano una vasta selezione di gioielli, impreziositi da gemme di grande valore. La produzione orafa dei Selgiuchidi, Fatimidi, Nasridi, Ottomani e Moghul è più conosciuta ed è stata studiata in dettaglio, grazie al maggior numero di pezzi disponibili e giunti integri fino a noi.

Riferimenti bibliografici

S. Bağcı and Z. Tanındı, ‘Art of the Ottoman court’ in D.J. Roxburgh, editor, Turks: A Journey of a Thousand Years, 600–1600, London, 2005: 260-375.

Department of Islamic Art, ‘The Art of the Nasrid Period (1232–1492)’, in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nasr/hd_nasr.htm (October 2002) (April 8, 2023).

Department of Islamic Art, ‘Turkmen Jewelry’, in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/turk/hd_turk.htm (August 2011) (accessed April, 2023).

L.S. Diba, Turkmen Silver: Jewelry and Ornaments from the Marshall and Marilyn Wolf Collection, New York, 2011.

D.M. Dunlop, ‘Sources of Gold and Silver in Islam According to al-Hamdānī (10th Century A. D.)’, Studia Islamica, 8, 1957: 29-49.

M. Jenkins, ‘Fāṭimid Jewelry, Its Subtypes and Influences’, Ars Orientalis, 18, 1988: 39-57.

M. Jenkins and M. Keene, Islamic Jewelry in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1983.

M. Keene with S. Kaoukji, Treasury of the World: Jewelled Arts of India in the Age of the Mughals, exhibition catalogue, British Museum, London, and other cities, London, 2001.

N.D. Khalili, Visions of splendour in Islamic Art and Culture, Corsham, 2008:132-39.

J.M. Rogers, Empire of the Sultans, Ottoman art from the Khalili Collection, London, 2000.

M. Rosser-Owen, Islamic Arts from Spain, London, 2010.

Y. Al-Saleh, ‘Amulets and Talismans from the Islamic World’, in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tali/hd_tali.htm (November 2010) (April 6, 2023).

M. Spink, and J. Ogden, The Art of Adornment: Jewellery of the Islamic Lands, 2 volumes, London, 2013.

C. Stewart, ‘Fatimid Jewelry’ in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/fatij/hd_fatij.htm (February 2018) (accessed April 6, 2023).

A. Topsfield, Visions of Mughal India, the Collection of Howard Hodgkin, Singapore, 2012.

S. Yalman, based on original work by Linda Komaroff, ‘The Art of the Seljuqs of Iran (ca. 1040–1157)’ in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/iselj/hd_iselj.htm (October 2001) (accessed April 6, 2023).

________________________________________________________

Roberta Marin, ha conseguito la laurea in Lettere Moderne con indirizzo storico-artistico all’Università di Trieste ed ha completato il suo corso di studi con un Master in Arte Islamica e Archeologia presso la School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) dell’Università di Londra. Ha viaggiato a lungo nell’area mediterranea e il suo campo di interesse comprende l’arte e l’architettura mamelucca, la storia dei tappeti orientali e l’arte moderna e contemporanea del mondo arabo e dell’Iran. Collabora con la Khalili Collection of Islamic Art e insegna arte e architettura islamica in istituzioni pubbliche e private nel Regno Unito e in Italia.

______________________________________________________________