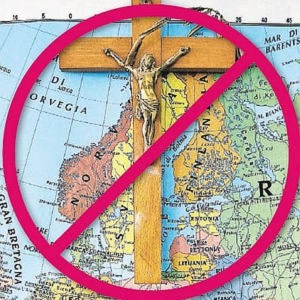

The procedure introduced with appeal No. 30814/06 by Mrs Soile Lautsi, ended on November 3, 2009, by unanimous decision of the judges of the ECHR that condemned Italy for the violation of article 2 of Protocol No. 1 and article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The main reason that led the judges of Strasbourg to condemn Italy is given by the fact that the presence of crucifixes in public schools is in contrast with the European Convention. The decision under consideration marked a historic turning point in the orientation of the Court which until then had taken a detached attitude towards the issues covered by our investigation

«So far, referring to the national margin of appreciation is the only answer that the European Court of Human Rights has been giving when the issue of banning religious symbols from the public space is at stake» [1].

In this sense, the decision fulfills the expectations as for the first time the Court of the Council of Europe takes a position on the display of religious symbols in public spaces. In the opinion of who writes, the sentence of the Court has had repercussions not only in Italy but also in other European and non European countries, consider as an example the decision of 1995 pronounced by the German Federal Court against the State of Bavaria regarding the exhibit of religious symbols in public schools, the Romanian case of 2006 concerning the exhibit of Orthodox symbols in public schools and finally the Turkish case of 2005, about the prohibition to wear the veil at the University of Istanbul.

The Lautsi case

Ms. Soile Lautsi, during the meeting of the Comprehensive State Institute «Vittorino da Feltre« Council attended by her two sons Dataico and Sami Albertin, raised the question of the presence of the crucifix and in general of religious symbols, in the classrooms, asking the removal because it violated the principles of secularism considered by the latter to be essential for the education of children.

Following the decision of the Council of the Institute to reject the request for removal of the crucifix from the walls of the classrooms, a decision based essentially on the two royal decrees of 1924 and 1928 [2] which actually provided for the presence of the crucifix, on July 23, 2002 Mrs Lautsi appealed to the administrative court of the Veneto region (TAR) against the school for violating the principle of neutrality of the State and the principle of secularism.

On October 3, 2002, a few months after the appeal was filed, the Ministry of Universities and Research issued a directive under which school leaders would have to guarantee the presence of the crucifix in classrooms [3].

Tar raised a question of constitutional legitimacy, suspending judgment and putting on record again the Constitutional Court, which in 2004 declared itself unsuitable for espressing its view regarding the issue because the provisions challenged before it were of a regulatory and not of a legislative nature.

The two provisions issued in 1924 and 1928, were never in fact canceled and consequently the presence of the crucifix in the classrooms was not in contrast with the supreme principle of secularity of the State enshrined in Articles 7 and 8 of the Italian Republic Constitution.

So the case returned to the regional administrative court which, on March 17, 2005, rejected the appeal of Mrs Lautsi, claiming in particular that the crucifix was a symbol of the history and cultural identity of the Italian society [4]. With sentence n. 5566 of April 14, 2006, the Council of State, appealed by the applicant, pronounced itself in favor of the Italian government, confirming that the crucifix was not only a religious symbol but was to be considered an integral part of the secular values of the Constitutional Charter [5].

Finally, after having tried unsuccessfully before the Italian courts, on November 27, 2006, Ms Lautsi appealed the European Court of Human Rights, denouncing the violation of Article 2 of Protocol No. 1 concerning the right to Education [6], Article 9 of the Convention on freedom of thought, conscience and religion and Article 14 on the prohibition of discrimination [7]. By judgement of November 3, 2009, the Court of Strasbourg unanimously decided that the exposure of crucifixes in Italian public schools was contrary to Article 9 of the Convention and it violated the religious freedom of children and the right of parents to educate their children according to their convictions. Having detected the aforementioned violations, the Court condemned Italy pursuant to article 41 of the Convention, to compensation of 5.000 Euros in favor of the applicant.

The pronouncement of the Strasbourg judges, claiming that the crucifix could have been interpreted as a predominant religious sign [8], stood in stark contrast to the previous decisions of the Italian courts.

The presence of the crucifix within educational institutions, in fact, points out that this environment has a religious connotation, to be linked in particular to the Catholic religion. This circumstance could, according to the Court, constitute an obstacle for non-believers and religious minorities.

The freedom to not believe is sanctioned by the European Convention on Human Rights and it also concerns religious practices and symbols that express particular beliefs. The ECHR Court believes that religious freedom and freedom to not believe should be guaranteed when there is a tendency of the State to impose its religious faith in public space.

The Italian reaction to the decision of the Court of Strasbourg on the Lautsi case

The Italian reaction to the decision of the Court of Strasbourg on the Lautsi case

First of all it’s necessary to point out that the pronouncement in question was received with great interest by the Italian public opinion, politicians and State officials, provoking reactions of various kinds. There have been cases of deputies, belonging to the extreme right-wing political forces that threatened Mrs Lautsi and severely attacked the sentence. A former Italian government minister went further, shouting during a broadcast that was on the RAI channel, «death to those people«, with reference to the applicant and her husband, and repeatedly claiming that «those international institutions (with regard to the European Court) have no importance».

Similar statements have been expressed by the mayor of a city in Northern Italy (who also holds the office of European deputy and belongs to the Northern League) who was much more critical using racial insults. The positions taken by important state officials are also of particular importance. It is worth mentioning the case of the former Minister of Education, Letizia Moratti, who publicly supported the request of the League and, in 2002, issued a directive for the introduction of the crucifix in schools [9], but also the draft law on living wills, supported by the government of the time and close to the requests expressed by the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

Beyond the statements raised, other factors that have generated such reactions is to be counted, ex multis, the growing fear towards Muslims, fomented also by the terrorist acts of recent years. In addition to the attitudes mentioned above, the Italian State has taken official actions, appealing the pronouncement of the judges of Strasbourg before the Grand Chamber pursuant to Article 43 of the Convention. The appeal brought by Italy has also been supported by other Member States of the European Convention on Human Rights, with a predominantly Catholic population such as Poland, Lithuania and Slovakia, which have taken positions in sharp contrast through their representatives with the pronouncement first instance of the ECHR Court.

By way of example, the case of the Polish parliament (SEJM), which officially invited the parliaments of the member States of the Council of Europe to oppose themselves to the judgment of the judges in Strasbourg; or even think of the case of the Lithuanian parliament (SEIMAS), which in turn upheld the appeal of the Polish parliament, highlighting that the ruling in question favored those who are opposed to any religious symbol pertaining to the European culture, without giving importance to the historical, cultural, religious context and the principle of free appreciation of the States [10].

Of particular relevance in this context is the attitude of the Holy See, which, following the publication of the decision of the ECHR Court , highlighted, through its spokesperson Eminence Federico Lombardi, the particular link between Christianity and European identity, claiming that « the Court ignored the role of Christianity in the formation of the European identity». [11]. Furthermore, by stating that «the European Court has no right to interfere with a question entirely related to Italy», it has given a strong political signal that goes beyond the competences proper to the position it holds.

The reactions of the other European Churches were equally strong. In particular, the Archbishop of the metropolitan city of Gdansk in Poland declared that «this was an attempt to wrest the faith from the hearts of the people». [12]. The Greek Orthodox Church through Archbishop Ieronymos, asked for the emergency meeting of the episcopal college of the Greek Orthodox Church, which condemned the decision of the Court for ignoring the role of Christianity in the formation of the European identity [13]. Finally, the Patriarch of Russia sent a letter of support to the Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, believing that the Christian inheritance of Italy and other European states must be removed from the examination of the European institutions:

«The Christian religious symbols present in Europe is a publicity of the European identity, without which the past, the present and the future of this continent are unthinkable The guaranteeing of a secular nature of the state must be used as a pretext for infusing an anti-religious ideology that conspicuously breaches peace in society and discrimination against Europe’s religious majority – Christians».

In this sense, the Patriarch granted «full and unconditional support» to the decision of the Italian government to appeal the ruling to the Grand Chamber as «European democracy must not incite Christianophobia, as the theomachist regimes did in the past» [14].

Finally, it’s worth mentioning the case of the Romanian Orthodox Church which, through the protests of the Pro-Vita Association for Children, sharply criticized the approach taken by the Court. The association in fact filed a petition to the Court of the EDU, considering the sentence to overcome the jurisdiction of the judges of Strasbourg [15].

The decision of the judges of first istance, who claimed that «the presence of crucifixes in compulsory public schools is at odds with the European Convention on Human Rights and the sensitiveness of European citizens «and that it constitutes an attack on freedom of conscience and the right of the individual to receive an education conforming to one’s religious or philosophical convictions» must be considered a strong political stance in terms of freedom of conscience and principle of secularity of the state.

Alongside the numerous convictions that we tried to explain, it should be noted that the sentence also received many plaudits. More than 100 Italian organizations have sent a letter of support, in relation to the orientation taken by the ECHR Court, addressed to the Council of Europe, the Parliamentary Assembly and the Court itself. The contents of the letter denounced the behavior of the Italian State, which had intimidated with vicious and violent responses not only the judges of the Court of Strasbourg but also the non-believers and those professing a faith different from the Catholic one.

The pronunciation of Strasbourg certainly represents a decisive step towards the affirmation of the principle of state neutrality and impartiality in religious matters, even if some members of the European Parliament have denounced the violation of the principle of subsidiarity. In fact, some parliamentarians such as Simon Busuttil, Mario Mauro and Manfred Weber, belonging to the group of the Partito Popolare Europeo, presented in 2009 a motion in defense of the principle of subsidiarity [16].

The resolution asked for the recognition of this principle and of the freedom of member States to display their religious symbols in public places, when these are representative elements of the identity and unity of the people [17]. In the de qua resolution, there was a complaint about the effectiveness of the sentences of the ECHR Court within the legal system of the European Union, and in this regard the Commission was invited to recognize the violation of the principle of subsidiarity that resulted from the sentence, violating the respect of national identities of the Member States. It seems interesting to point out that the Progressive Alliance group of Socialists and Democrats has declared it self in favor of the resolution condemning the Strasbourg ruling, unlike the radical left alliances and the Greens who voted against this resolution. These dissenting groups proposed a new resolution in which they claimed that «it should not be mandatory to show religious symbols in public and institutional spaces» [18] and they invited the member States to respect the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights, pointing out that the member States have a legal obligation to respect the judgments of the European Court. However, the proposal for a resolution, which had to be voted at the beginning of the new year, was removed from the agenda, avoiding an international conflict between the European Union and the Court of Strasbourg.

The question of exhibiting religious symbols in Italian schools

The theme of exhibiting religious symbols in public educational institutions in Italy, took place starting from the fascist period during which the religious sentiment of the majority of Italian citizens [19] was exploited to obtain power. With some provisions also called regulatory acts enacted in full fascist regime, between 1924 and 1938, a series of laws and decrees that damaged the rights of religious minorities were implemented. Among these we can remember the royal decrees; law n. 1159 of June 24, 1929 on permitted cults, which mainly concerned the Jewish community that in 1938 suffered the so-called “racial laws”. In this context the Fascist logic encouraged the formation of a close bond between the State and the Catholic Church.

The presence of the crucifix in schools, courtrooms and hospitals found a legal foundation also in the Constitution of January 1, 1948 which, while emphasizing the importance and value of personal and collective freedom, sanctioned the recognition of the right to religious freedom, extending it to all religious confessions, as the inviolable right of each individual, not only of citizens [20]. It should however be noted that paradoxically, neither the judgments No. 203 of 1989 and 13 of 1991 of the Constitutional Court, which reaffirm the principle of secularism of the State as the supreme principle of the constitutional order [21], nor the legislative constitutional changes, have scratched agreements, compromises, norms and laws issued on the subject of religious freedom during the Fascist period.

The Constitutional Court has clarified, with sentence n°195 of 1993, that through the principle of secularity it intends to guarantee the equal treatment of religious confessions and, with sentence n°334 of 1996 it specified that secularity must be understood as a mere non-denominationality of the State, to then again define it, with sentence n°235 of 1997, as an expression of religious neutrality that obliges the State to maintain an equidistance position from all religious confessions, as confirmed with sentence no. 508 of 2002.

Despite the orientation expressed by the Constitutional Court in the aforementioned rulings, even today, after 41 years, the removal of religious symbols, in respect of the secularity and the principle of equality seems a goal still impossible to achieve.

In 2012, the parents of some children who attended the elementary school posed the problem of the presence of the crucifix on the walls of the classes, complaining that the vision of that symbol as a religious element could have encouraged a climate of unease and religious prejudice towards children [22] belonging to religions other than Catholic and could have hurt their sensibility [23].

In a similar sense it seems interesting to remember that in 2014, the parents of some children of the Islamic religion, opposed themselves to the blessing by the parish priest on the day of believing that such behavior was not appropriate for a public school.

Among the other examples that make up the case studies about exhibiting religious symbols in public places, is the case of Marco Montagna, an electoral scrutineer of the polling station No. 71 at the hospital S. Croce di Cuneo, who in 1994, refused to take up the position in the absence of an effective respect for the name of the constitutional principle of secularity of the State, due to the presence of the crucifix in the polling station [24]. The court of L’Aquila, following an appeal brought on 23rd October 2003 by Mr. Adel Smith for the removal of the crucifix from a classroom of the primary and secondary school “Antonio Silveri”, with precautionary ordinance n° 1383/2003, accepted the appeal and ordered the removal of the exposed crucifix. Also in the political sphere there have been many parliamentary questions, concerning the issue that’s here. We can remember the ex-plurimis questions of 1996, promoted by the senators Tana De Zulueta, Alfonso Mele and of Carlo Benedetti; of Senese, Saraceni, Paissan, Gardiol and De Benetti in 2000.

The episodes mentioned above have helped to turn the spotlight on the subject of our examination becoming a central point of the media debate both within the mastheads and the political debate, in which they found strong opposition from political sides that have openly exposed themselves in favor of exhibiting the crucifix in public places, presenting motions at the municipal and regional level [26]. Think of the aforementioned case of the former minister of public education Letizia Moratti, who, in contrast with the order of the Court of L’Aquila, has publicly supported the Lega’s request, issuing the directive for the introduction of the crucifix in schools [27].

In conclusion it may be noted that, despite the unequivocal orientation of the Constitutional Court, which has always required «the suspension of the mandatory nature of the presence of crucifixes on the walls of public schools» so far it has been impossible to adapt to the judgments of the same also due to political reasons that have made the Italian case quite relevant for other experiences, such as the German, French and Turkish one.

The German case forerunner of the ruling against the Italian state of the Italian context

The German case forerunner of the ruling against the Italian state of the Italian context

Of particular interest for the theme that is dealt with in this paper, the position of the German Federal Constitutional Court emerges, which in a decision of 1995 [28], changed the 1990 regulation of the State of Bavaria on exhibiting the crucifix in primary classes. The case originated from the complaint of a parent who claimed that the daughter had been traumatized by the exposure in the classroom, at about 60 cm in height, of the statue of Christ denuded and covered with blood [29]. Following the protests, the school decided to replace the statue with a smaller crucifix. The Bavarian Administrative Court refused to file the applicant’s complaint, therefore the latter resorted to the Constitutional Court. Although the Bavarian constitution contained regulations based on Christian values, in a ruling of August 10, 1995, the Court established that the presence of crucifixes in non-denominational public schools is illegitimate and violates the right to profess one’s own faith and freedom of conscience sanctioned by Article 4 of the Federal Constitution. It should however be noted that the Federal Constitutional Court had previously held that public school systems were excessively dominated by the religious aspect [30]. It is interesting to recall in a manner consistent with what has been said so far, a previous sentence of 1973, in which the Court had ordered the removal of the crucifix from the courtroom of Dusseldorf following the request from a citizen of Jewish origin, through his lawyer.

The Federal Constitutional Court, while recognizing the crucifix as a symbol of shared values and a constitutive element of the historical heritage and traditions of the European culture, also reiterated its religious function, highlighting the need to keep the religious life of the private sphere separate from the public sphere. Finally, it should be emphasized that the cancellation of the regulation on the presence of crucifixes in public schools, which sanctioned its unconstitutionality, had direct effects also in other states of Germany.

The reactions, political and otherwise, following the issuing of the previously examined pronouncements, make the German case and the Italian case particularly relevant also in the study of the Romanian experience.

Brief analysis of the Romanian case

The issue of displaying religious symbols in public buildings has also been raised in Romania. The case is that of Professor Emil Moise who in 2006, when her daughter attended the Academy of Fine Arts, made a request to the Romanian National Council for the fight against discrimination (CNCD) on the cancellation of the regulation about exhibiting religious symbols in the public school [31]. Ms Moise pointed out that the drawings depicting religious symbols with orthodox signatures, which decorated the walls of the school, were discriminating against non-believers and the faithful of other religions. The religious symbols had, in the opinion of Mrs Moise, negative repercussions on the development of the student’s consciousness and creativity, while transmitting values of submission [32].

Mrs Moise received support from the Centrul de Resurse Juridice and the National Council for the fight against discrimination, who signed a document urging the Ministry of Education to take action on the issue of the presence of religious symbols within the classrooms that, according to the aforementioned institutions, represented a violation of religious freedom and freedom of conscience.

The board of directors of the national council for the fight against discrimination, sided to support Ms. Moise claiming that the display of religious symbols in public schools constituted discrimination for minority faiths, it was therefore ordered on one hand the immediate removal of the exhibit of religious symbols, except for the hour of religious education, and on the other the formulation of a draft law designed to safeguard both the right of students to learn in respect of the secularization principle of the state, and the autonomy of religious cultures and respect for the religious diversity of children.

The event also had the support of the civil society, and in particular of non-governmental organizations and Romanian intellectuals, who signed a public petition in which they showed the Romanian government the need for a democratic and secular change [33].

The decision of the CNCD council and the reaction of civil society, opened a constructive debate at the national level that involved not only the Ministry of Education and that of Culture and Religious Affairs but also religious confessions, journalists, nationalist and populist groups .

The strongest opposition came from the Romanian Orthodox Church which, in a statement from the office of the Orthodox Patriarchate, severely criticized the decision taken on the removal of religious symbols from schools, deeming it unjustified and detrimental to religious freedom. At the decision of the CNCD, there were oppositions by the ministry of education, the ministry for religious affairs and some pro-life non-governmental associations, which gave rise to two different appeals. With reference to the first appeal of 11 June 2008, the Supreme Court of Cassation annulled point 2 of the CNCD inviting the Ministry of Education to prepare internal regulations concerning the display of religious symbols in public institutions.

Regarding the second appeal, the Bucharest Court of Appeal upheld the decision of the CNCD, confirming its legal correctness. The seventh-day adventist Church has also adhered to this second orientation, and this Curch confirmed that State institutions and public schools should not be promoters of religious ideologies, teachings and even less of the principles of a particular religion.

It is therefore to be noted that we are in the presence of two sentences of opposite orientation, regarding the display of religious symbols in public schools.

General contents on the Lautsi case and the resolution of condemnation of the European Parliament

General contents on the Lautsi case and the resolution of condemnation of the European Parliament

After focusing on the record of cases that challenged the display of religious symbols in the name of the principle of secularism linked to the guarantee of individual freedom of religion and conscience (see Consorti, 2014: 108) and on the reactions of religious and political groups and fundamentalist organizations against the restrictive measures of religious freedom in public institutions, it’s necessary to analyze the general arguments concerning the ruling by the ECHR Court and its condemnation by the European Parliament.

In the previous paragraphs we have in fact recalled some cases in which European parliamentarians had proposed to the parliament a resolution condemning the decision of the European Court, recalling the principle of subsidiarity and the doctrine of the margin of appreciation [34].

The principle of subsidiarity is enshrined in the protocol N°30 of 1997 [35] under which the application of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality takes place in accordance with the provisions and objectives of the treaty on the functioning of the European Union [36] with particular reference to the maintenance of the acquis communautaire which should guarantee and strengthen the institutional capacity of the European Union. We should highlight that on one hand, paragraph n°2 doesn’t prejudice the principles developed by the Court of Justice with regard to the relationship between domestic law and Community law, and on the other hand that paragraph 3 does not call into question the powers conferred to the European Community by the treaties. The intervention of the Court of Justice is legitimate in cases where the aims can be achieved more effectively at Community level.

However, it should be stressed that neither Protocol N°30 nor the treaties provide guidelines to establish the extent to which Community action can be pushed towards the display of religious symbols in public buildings. This gap can be understood having regard for a plurality of factors first among all the fact that the three treaties establishing the European community have not addressed the human rights issues because the fundamental aim of the European Union was economic integration . Subsequently, with the establishment of the EEC treaty, the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of nationality was foreseen and only in the 70s they began [37] to talk about the protection of human rights as a general principle that originates from international treaties and from the constitutional tradition of the member States [38].

Further progress with regard to human rights was achieved in 1986 with the establishment of the first treaty, called the Atto unico (Single Act), which includes in the national law not only the fundamental rights enshrined in the constitutions of the member States but also those provided for in the Convention for the Protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, as well as the European Social Charter.

Furthermore, Article F of the Maastricht treaty lays down that the Union respects the fundamental rights guaranteed by the European Convention and pursuant to Article 13 of the Treaty of Amsterdam, the Council is authorized to take appropriate measures to combat discrimination, with specific reference to faith and religion.

A further step on the reformulation of the provisions concerning human rights is the Lisbon Treaty which, paving the way to the Charter of Fundamental Rights, establishes that

1) The Union recognizes the rights, freedoms and principles of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which has the same legal value as the treaties.

2) The Union adheres to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. This accession does not affect or change the competences of the Union defined by the treaties.

3) The fundamental rights guaranteed by the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, and resulting from the constitutional traditions common to the member States, are part of the law of the European Union as general principles.

The principle of subsidiarity and the doctrine of the margin of appreciation

The principle of subsidiarity and the doctrine of the margin of appreciation

The principle of subsidiarity and the theory of the margin of appreciation constitute two aspects of a more general principle of proximity [39] of the protection of the Convention and of the action of the European Union in general. While the principle of subsidiarity refers to a rule of precedence, which can be deduced ex multis by article 35 of the ECHR, pursuant to which the fact that a period of six months from the definitive sentence has been a condition of admissibility of the appeal before the judges of Strasbourg, the doctrine of the margin of appreciation pertains to an attitude of c.d. self restraint of the ECHR Court, later borrowed by the Court of Justice [40].

A fundamental precept of the European community since its inception, the principle of subsidiarity has mainly concerned issues related to the economic integration of the member States, only subsequently affecting the human rights field, following the inclusion in the treaties of the European community, even if it should be pointed out that European legislation was limited to establishing the supremacy of national regulations in this field [41].

As for the doctrine of the margin of appreciation, it should be remembered that the decision on the Lautsi case had been appealed to the Grand Chamber, invoking the application of the doctrine of the margin of appreciation as a universal standard of legal pluralism. Indeed, the ECHR establishes universal standards within which a margin of choice is left to the member States:

«Every society is entitled to (a) margin of discretion granted to the States in the solution of conflicts arising between individual rights and national interests or that come from different moral orientations» [42].

The doctrine of the margin of appreciation arises from the jurisprudence of the Court of Strasbourg and is based on some cardinal principles [43] also consecrated in the Convention, consider the principle of personal freedom and security (ex Article 5), the respect for family life (Article 8), freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Article 9), of expression (Article 10), to the principle of non-discrimination (Article 14).

This doctrine is a form of self-limitation of European bodies concerning political issues that form the basis of sovereignty. Although there is currently a certain degree of uniformity regarding the issues of freedom of political expression and protection of vulnerable groups, it should be noted that there is a great deal of decision-making autonomy for States in establishing strategies and balancing issues of public interest, not to mention the possibility for them to rely on the experience of the Strasbourg Court.

An emblematic case of the above mentioned theory was, for example, the Handyside v. United Kingdom case [44] where, in relation to the publication of a book considered obscene, the State provided clarifications on what behaviors and attitudes should be considered morally acceptable.

The doctrine of the margin of appreciation is not explicitly recognized in the European Convention, but its operation can be derived from some provisions contained within it, which refer to the national legislation for the limitations or modalities of exercising certain rights [45].

Returning to the case that concerns us, it’s to be considered that the complained violation of the doctrine of the margin of appreciation, raised by Italy, is unfounded.

The Court of Strasbourg has the task of ascertaining the correct application of the principle of margin of appreciation by the State. Having regard to the theme of religious freedom as per article 9 of the ECHR, the Court has the task of verifying the legitimacy or otherwise of the restriction of rights exercised by the State in implementation of the doctrine of the margin of appreciation and of ascertaining that such restrictions comply with the second paragraph of Article 9 above. The verification of the legitimacy of the restrictive measure relates to the existence of a legal basis of the same, to the aim pursued by the measure (which must concern issues of public security, issues concerning the protection of the rights and freedoms of others, public health, etc.) and finally it concerns the ascertainment of the proportionality of the restrictive measure with respect to the aim [46], specifying that the de qua proportionality will exist when the restriction proves to be necessary for the maintenance of the democratic state. The task of the Court translates in fact into the execution of the c.d. proportionalitytest which consists in evaluating the impact of the restrictive measure on the law of the State and the so-called strido sensu proportionality, according to which the choice of the restriction must be made taking care to choose the least restrictive measure. In addition to assessing the proportionality of protected interests [47], it should be specified that the de qua measure must be motivated.

In conclusion, it does not seem possible to agree with those who argue that in the Lautsi case a violation of the doctrine of the margin of appreciation has been perpetrated. The Belgian judge Tulkens, the only dissenting judge of the decision of the Grand Chamber on the Sahin case of 2005, stated in this regard that:

«The question raised in the appeal, for the right to freedom of religion guaranteed by the Convention, is obviously a matter not only local, but involving all the member States. European supervision cannot be involved by invoking the mere violation of the principle of discretion» [48].

With reference to the Italian question on the crucifix, it is necessary to establish whether the balance between complex rights has been duly considered, as underlined by Isabelle Rorive [49], who pointed out that this aspect is one of the major critical issues of the ECHR, considering that very often the Court of Strasbourg was criticized for relying on the doctrine of the margin of appreciation in addressing issues related to cases of display of religious symbols.

In conclusion, it’s necessary to ask first of all whether the debate on the display of religious symbols was an entirely procedural or rather substantial question and whether the presence of religious symbols in educational institutions was compatible with the universal standards on fundamental rights and freedoms.

The removal of religious symbols to protect the public interest

The removal of religious symbols to protect the public interest

In an attempt to examine the reasons for the progressive orientation taken by the ECHR Court on the Lautsi case, it’s necessary to note that the Court’s decision was not only affecting Italy, but was addressed to all the public schools of the member States.

The rights of children are guaranteed primarily by the European Convention on the exercise of Children’s Rights, signed by the Council of Europe in 1996 and containing in article 2 a catalog of rights for minors, but also by the ECHR itself which establishes the protection of the rights of the child mainly in the educational sphere. We therefore have two levels of child protection in terms of education:

a) Firstly, it’s established that States cannot indoctrinate and educate children as opposed to parents’ beliefs:

«The right to education cannot be denied to anyone. In exercising its functions in the field of education and teaching, the State must respect the right of parents to provide for such education and teaching according to their religious and philosophical convictions» [50]. Think about, in this regard the case of 2007 that saw as protagonists the gentlemen Hasan Zengin and Eylem Zengin against Turkey. The applicants had complained that the methods of teaching of compulsory classes of culture and religious ethics violated the rights guaranteed by Article 2 of Protocol No. 1 and Article 9 of the Convention [51]. The case has become a fundamental point of reference for the protection of freedom of thought, conscience and religion, and around these freedoms international jurisprudence has imposed impassable limits on governments to avoid the indoctrination of children to favor on the contrary a neutral education [52] from the religious point of view.

Religious education can indeed be a subject provided for in educational plans but it must provide for the teaching of history of the regions and of the different beliefs developed in social groups.

b) The second level of tutelage concerns the best interests of children enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In this regard, it’s necessary to recall the case of Kjeldsen Busk Madsen and Pedersen c. Danimarca who, in 1976, on one hand traced the guidelines of the Court regarding respect for the religious and philosophical convictions of the parents and on the other the limits within which the State can pursue the fulfillment of the obligations arising from the ECHR [53]. In this case, the parents had expressed their intention to prevent their children from attending sex education classes as conflicting with their religious beliefs. However, the Court had established that it’s the duty of the State to provide the pupils with the necessary information so that they can take care of themselves and others [54] and also pointed out that the inclusion of sexual education in school programs was not intended to limit a particular vision of the way of thinking nor to favor a specific type of sexual behaviour [55].

Similar considerations were made in the Dahlab c. Switzerland case in 2001, which saw as a protagonist a primary school teacher converted to Islam, who, following the refusal to remove the veil in the classroom, as requested by the general Director for the education of the Canton of Geneva, was expelled; or still think about the Dogru c. France case concerning two Muslim students who refused to take off their veils during the time of physical education. In both cases the Court has endorsed the decision of the States to condemn these attitudes under the principle of neutrality [56].

In this regard it does not seem superfluous to highlight the difference between the limitations on the use of religious symbols in schools, necessary to ensure the free development of personality and intellectual abilities of children and to ensure them a neutral education, and the limitations that have the purpose of protecting the participants from the educational process itself. As we have seen, in the Dahlab c. Switzerland case, the Court has confirmed the existence of the right of the Swiss State to prohibit a public employee from exercising their religious beliefs when such behaviour conceals intents of proselytism [57]. In an identical case, Leyla Sahin c. Turkey of 2005, the appellant underwent disciplinary proceedings by the University of Istanbul for refusing to obey the internal regulations of 1998 concerning the prohibition of wearing the headscarf during classes and during the examination.

The applicant appealed to the Court of Strasbourg for the violation of the freedom to express her own religion, also highlighting that in her previous experience at the public University of Bursu, no one had forbidden her to wear the veil. The Court established that there was no violation of Article 9 of the European Convention [58] by the University of Istanbul as the Turkish State was entitled to take the necessary measures to maintain public order and to establish when the veil worn in public institutions could represent or not a political position.

What is certain is that the automatic association of the Islamic veil with the Islamic ideology constitutes a risk for democracy as well as a serious violation of religious freedom.

Furthermore, in its decision the Court failed to assess the proportionality of the measure taken by the Turkish State, because in that case it would have undermined the internal regulations of the University.

In the light of these considerations, there is an almost contradictory orientation of the ESHR Court in the decision of the Dahlab and Sahin cases, with respect to the orientation adopted in the Lautsi case where it was also emphasized that parents’ right to educate their children cannot be translated into the mere arbitrary will to provide education suitable to their ideologies but it must instead consist of educational behaviours that are consistent with respect for the values of the democratic society [59].

A wavering and sometimes contradictory attitude is therefore noticeable on the part of the Court, which on one hand affirms the neutrality of the State in religious matters, considering that the veil worn in public schools contrasts with the principle of neutrality and on the other it condemns the display of crucifixes in public schools. Under the first aspect, the Court wants to affirm a positive dimension [60] of the State avoiding to transform educational institutions into religious places. By way of example, it is recalled that in countries such as France and Germany restrictive rules were introduced with respect to religious events in public schools, see the judgment of October 25, 2017 regarding the removal of the crucifix from the monument of the Holy Father Wojtyla in France or the Swiss law on public education which forbids teachers to show off their religious orientation in front of the students, considering this behaviour to be contrary to the principle of neutrality and secularism.

From the second standpoint instead, in the reasoning of the Second Section of the Grand Chamber, deciding on the case of Lautsi, it affirmed that a Christian religious symbol on the wall of a school doesn’t violate the principle of secularism but instead favors the sharing of ideas and visions in the perspective of a pluralist society.

In the opinion of the writer, the decision of the Court to consider legitimate the displaying of the crucifix in public schools as an essentially passive symbol, unable to threaten or indoctrinate the pupils, is not entirely acceptable.

It’s not indeed clear in which contexts the crucifix can be considered a passive symbol, not suitable to influence the freedom of conscience of the subjects not even the recall of the doctrine of the margin of appreciation can dispel doubts in this sense.

The judges in Strasbourg accepted Italy’s appeal even though they conceded that there was no consolidated and uniform orientation on the issue and placed a series of doubts partially collected by Judge Malinverni, who raised two orders of questions. Firstly, it was asked whether a concrete implementation of Article 2 of Protocol 1 could be done, since the provision in question appears to concern only the most professed confessions in individual countries. Secondly, it was asked whether the doctrine of the margin of appreciation has the same applicable scope when it comes to respecting Article 2 of Protocol 1 and when instead it’s a question of refraining from applying it. To both questions Dr. Malinverni gave a negative answer, as Article 2 of Protocol 1 of the Convention limits the margin of appreciation of the States in a certain sense.

What is indisputable is that the decision of the Lautsi case has provoked quite a few polemics seeing on one side the Catholics, or those who are close to the Catholic Church, who have received with great favor the pronunciation of the judges of Strasbourg [61], on the other the laity and all those who stood up for the protection of minority religions.

The ECLJ director, Gregor Pubbinck, also spoke in the debate, denouncing the imposition of attempts at secularism in Europe in contrast with the values of pluralism and respect for cultural diversity.

The absurd assertion according to which the sentence of the Strasbourg judges would lead to a series of social, cultural and religious transformations in Europe is only one way, in the opinion of who writes, to elude and conceal the substantive content of the sentence, which has the noble purpose of protecting the rights of believers as well as those of non-believers.

It’s to be assumed that the pronunciation of the main object of our work has the dual aim of guaranteeing the safety of childrens’ rights to receive an education free from religious, political etc., conditioning and to defend the free choices of minorities from the pressures of majorities.

However, it remains to be questioned whether the ruling by the ECHR Court and in particular the reference to the doctrine of the margin of appreciation and the principle of subsidiarity as corollaries of the principle of proximity of the individual States has obtained the result of imposing important restrictions on religious minorities, to the detriment of safeguarding the rights and freedom of Christian majorities.

Dialoghi Mediterranei, n. 30, marzo 2018

[*] The European Court of Human Rights was established by the European Convention for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, signed in Rome in 1950, to ensure its implementation. All 47 members of the Council of Europe join. See http: //www.coe.int.

Abstract

Il presente elaborato si propone di analizzare la tematica concernente l’esposizione dei simboli religiosi in luoghi pubblici, con particolare riferimento agli edifici scolastici, partendo dall’esame della pronuncia della Corte europea dei diritti dell’uomo sul caso Lautsi c. Italia.

L’articolo oltre ad analizzare le implicazioni che scaturiscono dalla giurisprudenza della Corte EDU, prende in considerazione le principali argomentazioni del ricorso proposto dall’Italia e la risoluzione di condanna del Parlamento europeo, richiamando il principio di sussidiarietà e la dottrina del margine di apprezzamento. L’indagine verrà svolta soffermandosi su tre casi riguardanti l’esposizione dei simboli religiosi: il caso Lautsi del 2009, il caso Baviera del 1995, ed infine il caso Romeno. I tre casi, anche se sottoposti all’attenzione della Corte in periodi e contesti differenti, hanno in comune l’oggetto del ricorso, ovvero l’esposizione del crocifisso nelle scuole pubbliche. L’obiettivo dell’articolo è quello di esaminare le implicazioni procedurali e sostanziali che scaturiscono dal ricorso, in applicazione del principio di sussidiarietà e della dottrina di margine di apprezzamento, partendo da due domande di fondo: a) se il dibattito sull’esposizione dei simboli religiosi sia una questione del tutto procedurale o sostanziale e b) se la presenza dei simboli religiosi nelle istituzioni scolastiche sia compatibile con le libertà fondamentali in tema di diritto all’istruzione e libertà di coscienza.

Notes

[1] Article 118 of the Royal Decree No. 965 of April 30, 1924 (Internal regulation of the councils and of the royal insitutes of secondary education) and Article 119 of the Royal Decree No. 1297 of April 26,1928 (General Regulation on the services of primary education).

[2] Directive No. 2666 of October 3, 2002 of the Ministry of Education, University and Research

[3] TAR Venezia, sentence of 17 March 2005. n.1110 / 2005, http://www.federalismi.it/ApplOpenFilePDF.cfm?artid=17792&dpath=document&dfile=22032011171925.pdf&content=TAR+Sentenza+del+17/03/2005,+in+tema+di+crocifisso+(Lautsi+TAR+Veneto)+-+documentazione+-+documentation+-+

[4] Council of State, sentence no. 556 of 13 April 2006. http://federalismi.it/ApplOpenFilePDF.cfm?artid=4056&dpath=document&dfile=17022006041629.pdf&content=Consiglio+di+Stato,+Sentenza+n+556/2006,+In+materia+di+laicità+dello+Stato+e+di+esposizione+dei+simboli+religiosi+negli+ambienti+scolastici+-++-++-+

[5] Article 2 of Protocol No. 1 guarantees: «The right to education cannot be rejected to anyone. The State, in the exercise of the functions it assumes in the field of education and teaching, must respect the right of parents to ensure such education and teaching according to their religious and philosophical convictions».

[6] Content of article 14 «The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms recognized in this Convention must be guaranteed without any discrimination, in particular those based on sex, race, color, language, religion, political or other kind of opinions, national or social origin, belonging to a national minority, wealth, birth or any other condition».

[7] The Lautsi contro l’Italia case (appeal n. 30814/06). Available at: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/tkp197/view.asp?item=2&portal=hbkm&action=html&

[8] Directive n. 2666 of October 3, 2002 of the Ministry of Education, University and Research.

[9] Committee on Foreign Affairs Statement on the Judgment by the European Court of Hu-man Rights on the Display of the Crucifix in Italian Classrooms, available online at http://www3.lrs.lt/pls/inter/w5_show?p_r=4028&p_k=2&p_d=94116.

[10]Italy school crucifixes ‘barred’,” BBC News, available online 3 November 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8340411.stm.

[11] Italy unites to condemn crucifix ruling,” Radio France International, available online at http://www.france24.com/en/en/node/4917686?quicktabs_1=0.

[12] Malcolm Brabant, “Religious Symbols,” BBC News, 13 November, 2009, available online at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/video_and_audio/8423027.stm.

[13] Available at: http://www.interfax-religion.com/print.php?act=news&id=6675; Russian Patri-arch protests court ruling to ban cross from Italian schools,” Interfax, 26 November 2009, available online at http://www.interfax- religion.com/?act=news&div=6675.

[14] Pro-vita Bucureşti solicită CEDO rejudecarea cazului Lautsi vs. Italia,” available online at http://provitabucuresti.ro/Advocacy/cedo-italia-lautsi-crucifix- scoli.html.

[15] For this quote and other motion quotes below, see the Motions for resolution available at http://209.85.129.132/search?q=cache:yqkd_icr2TUJ:cm.greekhelsinki.gr/uploads /2010_files/ghm1252_enooume1_omades_ek_thriskeftika_symvola_eng-lish.doc+ %E2%80%9Cthe+European+Court+of+Human+Rights+is+not+a+part+of+the+le-gal+sy stem+of+the+EU%E2%80%9D+lautsi&cd=2&hl=en&ct=clnk.

[16] Motion for a Resolution,” available online at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/get-Doc.do?pubRef=- //EP//TEXT+MOTION+B7-2009-0277+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN.

[17] Motion for a Resolution,” available online at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/get-Doc.do?pubRef=- //EP//TEXT+MOTION+B7-2009-0277+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN.

[18] P. Conforti, Diritto e Religioni, Laterza, Bari-Roma, 2012: 14.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Sentence of the Constitutional Court No. 508 of 2000 http://presidenza.governo.it/USRI/uf-ficio_studi/normativa/sentenza_508_2000[1].pdf.

[21] https://www.uaar.it/uaar/campagne/scrocifiggiamo/24.html.

[22] https://www.uaar.it/uaar/campagne/scrocifiggiamo/25.pdf.

[23] Marcello Montagnana was convicted by the Pretore of Cuneo under penalty of Lit. 400,000 of fine for the offense referred to in article 108 d.p.r. 30.3.1957, n. 361 – following the judgment of 28.04.1999 of the Corte Appello of Turin; Court of Cassation – Section IV Criminal Court Judgment of 1 March 2000 439/2000 – the dismissal of the appeal.

[24] At the Chamber, the Bricolo deputy proceeded to present a law proposal to reintroduce the crucifix

[25] Directive n. 2666 of 3 October 2002 of the Ministry of Education, University and Research.

[26] German Federal Constitutional Court, 16 May 1995, Kruzifix-decision, «BVerfGE» 93, 1.

[27] According to the description made by the CEDH.

[28] Being explicitly based on Christian norms, requiring the inclusion of Christian songs in music classes, designing curricula around Christian values etc.

[29] He has since become the leader of the association Solidarity for Freedom of Conscience.

[30] For a presentation of the case and especially the responses to it, see Horváth and Bakó, Religious Icons in Romanian Schools.

[31] G. Andreescu, Prezenţa simbolurilor religioase în şcolile publice: o bătălie pentru viito-rul învăţământului, in «Noua Revistă de Drepturile Omului» 2.4 (2006).

[32] The margin of appreciation doctrine is based on some key principles [1]: the ECHR establi-shes universal standards within which a margin of choice is left to the member States. Also available in::https://www.filodiritto.com/articoli/2016/05/la-corte-edu-e-il-margine-di-apprez-zamento-applicato-ai-simboli-religiosi-due-pesi-per-una-stessa-misura.html

[33] Treaty Establishing the European Community.

[34] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12008M%2FPRO%2F02

[35] O.J.L 169/1, 29. 6. 87.

[36] Rodoljub Etinski, Retrospective and Prospective of Human Rights in the European Union, in «Noua Revistă de Drepturile Omului» 4.3 (2008): 7.

[37] pp. 2. Available at : http://www.cortecostituzionale.it/documenti/convegni_seminari/con-vegno_20_settembre_2013.pdf.

[38] pp. 2. Available at : http://www.cortecostituzionale.it/documenti/convegni_seminari/con-vegno_20_settembre_2013.pdf.

[39] These national norms must be in compliance with the standards set by the European Convention. In fact, most EU countries have rendered the Convention apart of domestic law. The paradox of statements invoking subsidiarity as an EU principle was that in a possible application of domestic legislation against Union law the ECHR would be the superior norm.

[40] Eyal Benvenisti, “Margin of Appreciation, Consensus and Universal Standards”, New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 31 (1999): 843-4.

[41 S. Mancini, European supervision taken seriously: the controversy about the crucifix be-tween the margin of appreciation and the counter-majoritarian role of the Courts, in «Giur. Cost.», 2009, 5: 4055 ss

[42] Handyside houses v. United Kingdom, App. No. 54993/72, 1976

[43] Anro, I. The margin of appreciation in the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union and of the European Court of Human Rights, cit.: 4, available at: http // old.unipr.it / arpa / dsgs / MD / margin% 20di %% 20apprezzamento.pdf.

[44] L. Mezzetti, Rights and Duties, Giappichelli Torino, 2013: 93.

[45] Greer, S, The margin of appreciation. Strasbourg: Council of Europe; Bhuta, N., Two Concepts of Religious Freedom in the European Court of Human Rights (December 2012), SSRN: htpp / ssrn.com / abstract = 2201483 orhttp: //dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2201483.

[46] Rorive, «Religious Symbols in the Public Space», 2682.

[47]http://cardozolawreview.com/Joomla1.5/content/30-6/RORIVE.30-6.pdf.

[48] Council of Europe, European Convention on Human Rights, 1952 (http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ITA.pdf).

[49] The case of Hasan and Eyelem Zengin v. TurkeY, http://www.aihmiz.org.tr/?q=en/node/94

[50] Manfred Nowak and Tanja Vospernik, «Permissible Restrictions on Freedom of Religion or Belief» in Facilitating Freedom of Religion or Belief, eds. Tore Lindholm, W. Cole Durham, Bahia G. Tahzib-Lie, 171 (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff, 2004).

[51] Cf. P. Tanzarella, The margin of appreciation, in “Rights in action”, edited by M. Cartabia, il Mulino, Bologna, 2007: 149 ss. While on one hand this «flexibility» allows States to ba-lance the obligations of the Convention with other national needs, on the other it creates many problems in the event of failure or unsatisfactory implementation of the Court’s judg-ments.

[52] Case of Kieldsen, Busk Madsen and Pedersen v. Denmark (Application no. 5095/71; 5920/72; 5926/72).

[53] On the Kjeldsen and Angelini (see below) cases in relation to non-indoctrination – Geraldine Van Bueren, The International Law on the Rights of the Child (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1998): 160-2.

[54] Dogru v. France (Application No. 31645/04)

[55] Mrs. Dahlab was appointed primary-school teacher by the Geneva government, after which abandoned the Catholic faith and converted to Islam. The Director General prohibited the applicant from wearing an Islamic headscarf in the performance of professional duties.

[56] A. Nieuwenhuis, “European Court of Human Rights: State and Religion, Schools and Scarves. An Analysis of the Margin of Appreciation as Used in the Case of Leyla Sahin v. Turkey, Decision of 29 June 2004, Application Number 44774/98”, European Constitutional Law Review 1.3 (2005).

[57] C. Bîrsan, Convenţia europeană a drepturilor omului. Comentariu pe articole. Vol. I: Drepturi şi libertăţi, Bucureşti: C. H. Beck, 2005: 1071.

[58] On the various conceptions in Europe of state neutrality with respect to religion, see Chris-tian Joppke, State neutrality and Islamic Headscarf Laws in France and Germany, in « Theory and Society» 36.4 (2007).

[59] A. Bodnar wrote La grande camera non si occuperà della Lautsi («The big room will not deal with Lautsi»).

[60] https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/statoechiese/article/view/2028/2267

[61] S. Mancini, Lautsi II: the revenge of the joining tolerance, Forum of Constitutional Note-books. Available at: http: //www.forumcostituzionale.itwordpress/images/stories/pdf/docu-menti_forum/giurisprudenza/corte_europea_diritti_uomo/0015_mancini.pdf

_______________________________________________________________________________

Shkelzen Hasanaj, dottore di ricerca in Scienze Politiche presso l’Università di Pisa. Collabora alle attività della disciplina giuridica del fenomeno religioso (IUS11) del Dipartimento di Giurisprudenza dell’Università di Pisa. È autore di diversi articoli scientifici in Italia e all’estero: Le sfide d’integrazione e dell’inclusione in Italia:Per un nuovo paradigma basato su Dinamicità e Differenziazione, in «Diritto e Religioni», n. 2, 2016:191-207; Vivere nella diversità: Sviluppo delle tesi interculturaliste in dialogo con il modello multiculturalista, in «The Lab’a Quarterly», n.1, 2017: 27-44; Multiculturalism vs interculturalism: new paradigm? (sociologic and juridical aspects of the debate between the two paradigms) in «Journal of Education & Social Policy», published in Vol. 4 No. 2, 2017, ISSN 2375-0782 (Print) 2375-0790 (online). In corso di stampa, A new model of intercultural integration in Italy: recognizing the differences with ad hoc principles of precedence, in «Journal American International of Social Science» (AIJSS).

________________________________________________________________

This site definitely has all of the information and facts I needed concerning this subject and didn’t know who to ask.