di Paola Barbuzzi e Jupinderjit Singh

di Paola Barbuzzi e Jupinderjit Singh

The shocking criminal cases [1] on honour killings reported in the UK in the late 90s onwards, predominantly from Middle Eastern and South Asian immigrant communities, have drawn attention to the way the victims have been brutally murdered and deprived of their fundamental rights in a liberal country, which champions and promotes cultural rights for all British and non-British within its territory.

Non-discrimination, equality, self-determination, right to life, right to freedom, no torture, which are some of the foremost fundamental principles of human rights present in the Universal Declaration of Human rights, are inexistent within some patriarchal and traditional families and communities in relation to women. Especially, when women are accused of dishonour, their lives can end with death. Honour killing against women continues to be interpreted and depicted by the press, social media and thus by the public opinion as an «evidence of an unassimilated character» of immigrants from Middle East and South Asia. The latter seems to prefer dealing their family affairs with “anachronistic” and obsolete cultural practices and values brought from their homeland instead of embracing the values of their adoptive country. As shame, humiliation, dishonour and disgrace fall upon a traditional family as a catastrophe, due to the inappropriate behaviours of their women, the killing becomes the most effective practice to justify the crime and restore dignity. What’s more, the murder is seen as a symbolic act of sacrifice for the safeguard of a traditional ideology, which strongly supports and defines the public and private representation of masculinity and femininity. Honour and shame are rooted in the social fabric of patriarchal communities as a gendered value system. Consequently, the honour killing practice is regarded as gender-based violence because it discriminatively and unequally targets women because they are women.

Given all that, in the first paragraph, the article will begin with a brief introduction of the paired concept of ‘honour’ and ‘shame’ coined by social-anthropologists in the 60s, which then will lead to sociological discourses on gender value system in which the killing is conceived and executed. Furthermore, another relevant aspect emerging from these debates is the misuse of cultural differences as a justification of oppressive and discriminative cultural practices, which will be addressed in the second paragraph. The cultural differences discourse will also include the human rights perspective and the importance of preserving and stimulating the employment of a ‘cultural rights’. In particular, how a liberal country withstands in dealing with illiberal immigrant groups [2] in the context of justice delivery. As the judiciary sometimes has privileged the cultural factors over the gender discrimination to understand and justify the honour killing practice. Consequently, the perpetrators use the cultural defence as a justification for their crimes.

In the third paragraph, we attempt to analyse the psychological dynamics that women, subject to honour – based abuse in London, endure when they perceive that their bodies are impregnated with «the so – called traditional unwritten» principles or codes, which seem to shape the conception of honour within the female bodies intrinsically. If this twisted gendered construct inflicts emotional and coercive pressure on women to behave in a way that is not theirs, however, it leads many of them to decide to break up with traditions consciously. Therefore, what is the sentiment that drives the “survival” women to go against their cultural traditions, despite the likelihood of being murdered for the honour by their family members? How do the NGOs assist these bravery women to succeed in their freedom? In response to these questions, we have been supported by an NGO, based in London, Sharan Project and its experience with the survivals. At last, an independent section, held by Jupinderjit Singh, will narrate a case of honour killing inflicted to an Indo-Canadian young lady Jaswinder Kaur “Jassi” Sidhu, who was murdered in Punjab, India. The killing was orchestrated by the mother and her uncle as Jassi brought shame to the family for secretly marring Sukhiwinder Singh Sidhu (nickhname Mithu).

Honour and Shame

Honour killing is still an issue practised in every corner of the world. It does not matter where women live, which culture and religion they come from, they have no escape or voice to change the destiny of their lives, mainly when they have already been shaped and set up by their family members. Through historical accounts, women have been consistently maltreated and deprived of the right to choose and draw their own identity with different characteristics from the male patriarchal inheritance. Subsided by the masculine ideology, women could hardly escape from heinous and barbaric acts of any sort of violence in the name of honour and shame. The latter had to be protected and preserved through moral conducts, which were specifically tailored to reinforce the male authority over women’s lives. The honour of the woman was intrinsically intertwined with the honour of the man (Abdelhadi, 2016) [3]. The same logic is still today accepted and recognised as a cultural custom by some traditional and patriarchal societies and communities. Therefore, within this patriarchal ideological context, it seems evident that the language of honour and shame acquires gendered connotations and models the social conduct of male and female in public and private sphere of their lives.

In the 60s, social-anthropologists, who were focused on value systems in the Mediterranean societies, introduced, as Charles Stewart states in his Honour and Shame (2013) [4], the gender-linked concepts of honour and shame, which function «as a collective representation»[5]. Men had to show and maintain honour through aggression, pride, boldness, physical strength, while women had to be submitted to their men with obedience, modesty and reverence. This social-conceptual representation of honour and shame, based on gender discrimination and inequality, has become a universal reference to interpret other cultures with similar social value systems. All this has allowed other disciplines, such as sociology, to come forward and explore the causes and reasons of honour-based abuse, in particular cases of honour killing, which have taken place in the western society since the end of the 20th centuries within immigrant communities deriving from Middle East and South Asia.

The perception of honour killing, which is regarded as obsolete and anachronistic in a society with liberal values, has produced a prejudicial narrative against Muslim community. The latter is perceived by the Media as the one who retains the exclusiveness of honour killing imported phenomenon, driven by]…[practice, and it is depicted as an « cultural and ethnic manifestations of murderous patriarchal honour» [6]. De-facto, cases of honour killing, occurred in the UK, show that Muslim women are the most exposed to honour-based abuse. However, criminalising an entire community of Pakistani or Kurdish or Bangladeshi for crimes, which are practised by a few nuclear families, would escalate into false interpretations and create a collective and prejudicial stigmatisation of these communities. The stigmatisation depicts Muslim communities to be more inclined to embrace violence against women than the no-violence and gender equality promoted by the western culture. Against this simplistic and dangerous interpretation and categorisation of cultures, which can quickly encourage racist repercussions and create further division among different cultures, some academic researchers have highlighted the perspective of the pervasive deployment of honour killing practised everywhere in the world. Thus, due to this characteristic, instead of understanding and finding responses on culture, honour killing should be treated as a form of violence against women experienced by all women [7].

Honour killing is a criminal practice that has been exercised, regardless cultural, social and religious identities since the most antic civilisations across the world. Men of any time have had the power to hold the lives of their women and create conditions to kill them within a household and elsewhere. From the time of the Code of Hammurabi to the Ancient Rome, Middle Age until the current time immoral female behaviours have continued to be seen as an insult to the male honour. Losing authority over a woman was and still is considered in some traditional and patriarchal families unthinkable and outrageous. The misconduct of a woman, or the mere perception that she may have undermined the family honour, is enough to trigger the crime. When a patriarchal family recognises itself with the value system of honour and shame, its social behaviour is entirely constructed on the division of the role of man and woman, and this neat division allows the family to build up its reputation and status within the community. Therefore, a deviant or a rebellious woman would be deemed the destroyer of family honour and bring shame, humiliation and embarrassment.

A woman’s conduct is a family matter. Male family members such as the fathers, brothers, uncle, cousins and husbands have to guard women’s honour and police them, as expected by a patriarchal value system. When suspicions arise, the women become the target of violence. Hassan an errant woman would jeopardise the ability of her ]…[observes that« male relatives to hold their head up in society». Indeed, if a male relative loses supremacy and control over his women, this «implies a loss of masculinity, that is more costly to the man than woman’s life» [8]. Therefore, the act of killing becomes necessary to remove the shame, which the deviant woman has brought the family in, and restore honour and reputation. Within this policing environment, women’s destiny is entirely constructed and dependent on severe, physical, psychological and emotional pressures. Their behaviour and sexual conduct must follow precise rules that express submission to the family’s beliefs on how to keep intact the perfect image of a modest and decorous woman. In this regard, the figure of the mother is important. When a daughter brings shame into the family, the mother would be the first person to be criticised for her daughter’s misbehaviour. She is the one who has to teach her daughters how to be submissive, reserved and stay a virgin until the marriage. Moreover, a controversial aspect of mothers and other female members within honour killing crimes is that they can inflict violence against their rebellious daughters, sisters or daughters-in-law. The female loyalty to patriarchal rules is regarded as a form of subordinate cooperation to mediate and «secure their survival”. It is a vicious circle in which women must bargain to adapt themselves to a tyrannical male environment and at the same time they must help to perpetuate a tradition that is discriminative and unequal to them.

Testimonies provided by police officers and support workers have confirmed that women can have a significant responsibility in deciding the sorts of their appointed female victims. They can be directly active or passive. In the criminal case of Sabia Rani (R v Khan 1Cr App R 28) [2009] [9], Sabia, a teenage bride, was murdered by her husband in a moment of irrational rage, after she had endured an extended sicking period of ordeal ignored by the mother in-law and the two sisters-in-law, who shared the house. Their intent was to protect their son/brother. This omertà attitude is common among members of the family, who usually try to protect each other by keeping everything hidden and silent.

In the case of Sarjit Kaur Athwal’s death, the mother-in-law Bachan Kaur was instead the driving force of the family. She was the one who premeditated and organised along with Sukhdave Athwal the first son/husband the death of her daughter-in law/wife, Sarjit Kaur Athwal. According to the story told by the sister in-law Sarbjit Kaur Athwal in her book Shame, Sarjit’s death was a proper honour killing crime. Sarjit Kaur left England with her mother in-law for a trip in India, in December 1998. She never returned since then. When Sarbijt understood that Sarjit Kaur was murdered in Punjab, the emotional and psychological factors stopped her from going to the police. She was terrified that her family-in-law would murder her too. Despite this emotional fear, however, after almost ten years, Sarbjit’s testimony helped to convict and jail her mother-in-law and brother-in-law in 2007 at the Old Bailey for arranging Sarjit Kaur Athwal’s murder. This case like many others shows that the act of killing women for honour plays an important psychological role to other women of the family and also women of the community, when the killing is publicly known, because it is an educative deterrent. Women are given a warning about unusual behaviours, and these have consequences «[…] and inform them that violence will be used to modify transgressional behaviours» [10].

An appointed human rights, who is an expert on Extrajudicial, Agnes Callamard stated, in her report released on the 6th June 2017, that gender-based killings should be recognised as a form of arbitrary execution: «the fact is that gender plays an absolutely central role in predicting people’s ability to enjoy their human rights in general, and their right to life in particular» [11]. De facto, honour killing is a severe violation of human rights against women because it destroys the spirit of the universal connotation of human rights. The latter signifies «the recognition of the inherent dignity and equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family» [12]. Within this context of cultural rights, States have the responsibility to guarantee women and men their self-realisation and freedom from control, coercion, torture and abusive public and private conditions. Despite that, as already mentioned, many women around the world get murdered under the name of honour, due to the persistence of traditional and patriarchal ideologies. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), 5,000 honour killing practices occur annually around the world. It is believed that the actual number is much higher because this type of crime is often covered up by the family and community. Besides, most of the time the honour killing offence is reported as suicide [13].

Against discrimination and inequality, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1979, an international treaty to protect women’s rights. The purpose of the Convention was to ensure equal opportunities for women in all societies and guarantee freedom from any form of violence including harmful traditional and customary practices. Attention to «traditional attitudes by which women are regarded as subordinate to men» were drawn by the Committee on The Elimination of Discrimination against Women, established in 1982. After a decade, the Committee highlighted in the General Recommendation No. 19 of 1992 issues on family violence against female family members. It recommends the removal of national legislation “the defence of honour regarding the assault or murder of a female family member» [14]. In line with this position, the feminist perspective has vigorously criticised the use of cultural defence as a remedy for the perpetrators to «seek mitigation on the ground that the murder was committed as a consequence of protecting family honour». This way of reasoning, which portrays women not as victims but as transgressors of traditional cultures, has drawn the attention of Courts to the cultural motives rather than gender discrimination. De facto, it has been pinpointed by some scholars that in the English’s Courts murders in the name of honour have sometimes produced judicial discourses incongruous with the human rights perspective. In some cases, the defendants have had the chance «to plead not guilty to murder but guilty to manslaughter because of provocation» [15].

Provocation is stated in the Homicide Act 1957 in section 3, and it is recognised as an instrument of common-law defence. The latter has the function to analyse factors that may have provoked the person to lose self -control and induce him/ them to commit the crime, which is expected by the jury to assess «whether the provocation was enough to make a reasonable man do what he did». However, the reforms under the Coroner’s and Justice Act 2009 had stopped the misuse of self -control defence if this is done with the intention of revenge. Despite that, the lack of tailored legislation to deal specifically with honour killing and other forms of honour-based abuse still create confusion when in some cases the examination of honour killing privileges the narrative of cultural factors over gender violence. By doing so, the cultural defence undermines women fair treatment under the law and protection of women’s rights. What’s more, the cultural defence can send a wrong message to families and communities, which support honour killing, and see it as a favourable to their customary norms.

Some feminists have attempted to remove the impasse created by the cultural defence with the application of the “Mature multiculturalism” approach. The latter would fairly continue to take into accounts the cultural factors, as «the courts need to demonstrate multicultural sensitivity» [16], without though suppressing the gender violence element. The main goal is, however, to shift the attention to the violation of the human rights of the victim and regard the honour killing as gender-based violence, as it has already been stated in the General Recommendation No 12 of 1992. The latter was updated last year in July 2017 with the adoption of the General Recommendation no 35. The document unequivocally reinforces the prohibition of any form of gender-based violence against women, as a norm of customary international law; and it also provides a comprehensive strategy and solutions that all Stated parties should promptly implement at the national level [17]. Besides, it is imperative that «delays cannot be justified on any grounds, including on economic, cultural or religious ground»[18].

It emerges that awareness and pressure for a change are needed to help women who undergo gender-based violence in a liberal country like the UK. More importantly, women must feel that the judiciary fairly deals with honour killing cases from a human rights perspective because the suppression of the right to life for cultural reasons is unacceptable. Women like men living in patriarchal communities should have the right to participate in interpreting their own culture without being discriminated. In this regard, the duty of the State is to implement legal remedies where the culturalization of gender discrimination thrives.

Sharan Project

«The UK is the safest country for women», states Polly Harrar, founder of the national UK charity, Sharan Project, based in London. Violence against women in the UK has been managed over the past 20 years through awareness, intensive campaigns designed to sensitize the public opinion and emphasize on zero tolerance to «change specific aspects of the mainstream British Culture». This strategy has successfully helped to reduce cases of domestic violence, forced marriage and genital mutilations and turn such violence morally and socially unacceptable. However, «much more needs to be done against honour-based abuse», Polly continues, to protect women, especially young women between age 18-25, from being beaten, tortured, segregated, emotionally threatened, disfigured with acid to the actualization of the killing because of immoral “sexual” behaviours or western influences.

«The majority of women who contact us have already left their family and feel highly motivated to start a new life. Indeed, the main goal of Sharan project is to support women towards a leading independent life without fears». In 2008, Polly identified a gap in providing a service for those women from South Asian background who had been disowned or at risk of being disowned. Her expertise, especially natural skill to listen and understand women’s issues and the collaboration of other motivated professionals have successfully supported many women throughout these years to restart a new life from scratch. More importantly, these women have been able within an abusive family environment to strengthen themselves and leave home.

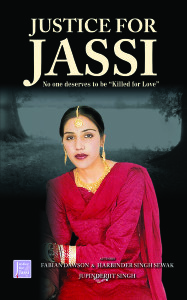

My brush with honour killing: Jupinderjit Singh (co-author: Justice for Jassi, a true honour killing case)

Born and brought up in Punjab, which despite being one of the more advanced state in India, treated women as second citizens, my first brush with the horror of mental and physical torture of women in the name of safeguarding theirs, as well as family’s honour, through the concept of purity of body and total subservience and imposition of parents/siblings on their choices in life, including mainly husband, came when I covered the internationally infamous Jassi honour killing case.

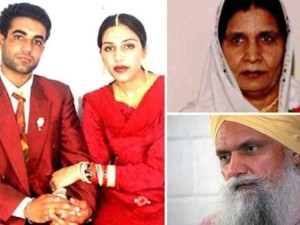

Jaswinder Kaur alias Jassi, a girl of Indian origin was born and brought up in Canada but under strict traditional and cultural environment. This meant she could not chose her profession, friends, dresses and most significant- her life partner. Jassi followed it all in complete obedience. She was called a paragon of traditional Indian/ Punjab virtues whenever she visited her native village called Kaunke Khosa in Jagraon sub-division of Ludhiana district of Punjab province. She covered her head with a dupatta (a long and thin cloth wore over breasts and head as a symbol of modesty); kept eyes lowered down and did not talk openly and freely to men, even male relatives. All those cultural barriers vanished when she sighted Sukhwinder Singh alias Mithu in her native village on a short visit in early 1996. She was just 16 at that time. The love at first sight developed into a serious relationship in four years of communication via letters and phone calls. It reached such an extent that Jassi made a dash to India from Canada (with the help of a female friend) and married Mithu in a Gurudwara (Sikh worship place) in Baba Bakala village against wishes of her parents and relatives on March 26. 2000.

Less than three months later, a group of contract killers killed Jassi and left Mithu for dead. Punjab Police has accused parents of Jassi of hiring the killers. The case propelled the issue of honour killing to international community. The world sat up at the full horror of it.«At least one honour killing is reported from Punjab every month. This does not mean that only one case happens. This means only one comes in public domain», says Puneet Grewal, who has recently earned a PhD degree on the menace of Honour killings in India. She has categorised 34 cases between 2008 and 2010 in her selected period of research.

According to a report released by the Government of Pakistan, «4,000 women and men were killed in the name of honour between 1998 and 2003» (United Nations General Assembly 2006). Another study conducted on domestic violence in Pakistan relates honour killing to the incident of a man who had killed another man and then was told by his father to murder his sister-in-law if he wanted to escape the death sentence (Hassan, 1995). Amnesty International 1999 report describes Honour Killing as extra-judicial punishment of a female relative for assumed sexual and marriage offences. «These offences, which are considered as a misdeed or insult, include sexual faithlessness, marrying without the will of parents or having a relationship that the family considers to be inappropriate and rebelling against the tribal and social matrimonial customs. These acts of killing women are justified on the basis that the offence has brought dishonour and shame to family or tribe». Adds Puneet, «A woman is always under the surveillance of the male members of her family. The body of a woman is not under her control. It is claimed to be the commodity and property of her father and family members before marriage and of her husband and his family members after marriage». Coming back to my experiences of reporting an honour killing case and later penning a book on it, I recall that when I first met Sukhwinder Singh ‘Mithu’, some 12 years ago, at his two room tenement sans a boundary wall, with un-plastered walls, with a roof without any safety projection to keep harsh rain showers at bay, and listened to his story of love with Jassi and her tragic murder, I was immediately filled with anger for the culprits.

I also remember the ache in my heart at the poor sight of the still stout and muscular young man, who, within a short time had experienced extreme heaven in the arms of his beloved and then hell at her separation. Her wife became a victim of honour-killing before his eyes while he was a living corpse. I felt lot of pity for him and I think I cried also later.

The tears did not cool down my anger for the culprits. I wanted to help Mithu. Strangely, I felt Jassi egging me on. I wanted to confront her mother Malkiat Kaur on how can a mother hand over her young daughter to the criminals (as claimed by cops). I also wanted to take on Jassi’s maternal uncle Surjit Singh Badesha for his alleged role in Jassi’s murder and the failed attempt to kill Mithu.

I wanted to ask sub-inspector Joginder Singh, who is convicted for abetting the inhuman crime and proximity to the 12 contract killers, only three of who are behind the bars now. I wanted to ask Joginder about his duty as a policeman and the oath he took to protect the law of the land and prevent injustice as was done to Mithu and Jassi. I wanted to confront him on how as a Sikh could he be part of such a heinous crime and forget the Sikh Guru’s teaching of helping the week and meek and standing up against the evil. I wanted to ask the contract killers on what all they bought for the money they took from Jassi’s mother. Though my experience as a crime reporter makes me understand that contract or hired killers were just faceless and nameless persons, who could have killed anyone for money. But didn’t their heart bleed for a single moment when Jassi was crying, beckoning God and humanity, and compassion in them when they were killing and ravaging her. Or when they left Mithu for dead in the fields and snatched his Jassi forever from him, didn’t they think even for a micro-second about the sin they were committing. Just few hundreds thousands of currency notes were enough to make them beasts. But above all, I wanted to ask the Canada based father and brother of for their mute acceptance of all that was happening around them. They were perhaps the only persons who could have intervened to stop Jassi’s mother in time or alert Jassi and Mithu When would they break their silence? They are still silent. Were traditions bigger than the life of Jassi?

I was no Hercules to help Mithu. But I had the power of the Pen and the influence of a Journalist. And that is exactly what I could do and I did. Doors started opening. The Punjab police which thought Mithu was alone realised there was someone backing him. And not just I, many journalists in Punjab and many from Delhi helped him. We could not prevent the inevitable. Mithu was finally framed in a false case of rape and jailed. Three years he spent in hell despite being an innocent man and a more innocent lover. He paid price for loving Jassi of higher socio-economic strata. And then the news reports seemed too less a platform to help him. At that moment I sat down writing a book about him. I used to meet him in the jail and saw his barrack. The book “justice for Jassi” began with Mithu telling his story and Jassi’s story through him. As providence had it or as I firmly believe and say, Jassi’s soul had it, a journalist sitting seven seas away in Vancouver , Canada, was suffering the same pangs of injustice to Jassi and Mithu. Fabian Dawson, a well known name in journalism owing to his world wide reports on anything that mattered had been to Punjab several times reporting and investigating Jassi’s murder and Mithu’s plight. He too visited him in the central jail Ludhiana. But unknown to me he too was doing a book on the love story that had gone awfully wrong. We both happened to travel by chance together in Gujarat when we shared our feelings for the tragic love story. And the book started taking shape. We both agreed it was one of the most poignant love story of modern times. It was not just another case in our journalistic life. It was a story which moved us from inside. It is a story which woke us up at the dead of night and we could hear the cries of help of Jassi. Fabian knew so much that happened in Canada with Jassi before and after her murder. And I knew stuff happening in Punjab.

Then, we needed lot of financial support and expertise of someone who bridged the gap between India and Canada , who understood the diverse cultures. This is where Harbinder Singh Sewak, chipped in. His knowledge of publishing, business skills and of Punjab and Sikh ethos ironed out many problems of understanding the complex issue. The three musketeers sat down to work with just one focus: to do our bit for far Jassi and to save Mithu from further troubles, at least , not of his own making. Jassi lived chasing a dream and she died doing so. She was a free bird. Her wings could not be cut. She had to be killed only to be stopped. She and Mithu were born miles away and nurtured in complete contrasting conditions. Mithu lived in poverty just next to the big house of Badesha’s, where Jassi’s mother had lived before she was married off to Canada. And once there, she was a ticket to many of her relatives to the “land of opportunities» that Canada was perceived as in Punjab. Mithu grew up in the shadow of Badesha’s property and influence in the village. Jassi’s mother and relatives may not have considered Mihtu and his family existed till Jassi came from miles of away and he along with Mithu scales those high walls of caste, status to try to live a life of their own. But while they narrowed the gap of continents between them, they could not win over the narrow hearts and eventually paid for it dearly. I had heard or read about the great love stories of Romeo and Juliet, Layla and majnu, sohni and mahiwal but nothing matches a love story that pans out in front of you. Their hearts beat for each other at the first sight. They managed to communicate in an age where there was no Internet or mobile phones in Mithu’s India and not even a land line phone. He used to travel in rain or in foggy winter at the dead of night to receive Jassi’s call at the public phone booth in Jagraon town, nearly 25 Kms away from his village house. They shared their happenings in over hundreds of love letters they exchanged. While translating those letters in to English for the book and the Canadian audience, I fought my tears at the sheer innocence of Jassi. I felt her drawing those roses on the love letters and felt the soft petals she drew. She did make hearts pierced by the Cupid’s arrow and some blood drops dripping down those. She may have never dreamt that one day her heart would bleed to death and there would be no one to come to her aid. She would have never thought that her Mithu would be left alone to battle out the world and live a lonely, desolate life.

The book, I hope would prevent further honour killings. On an average one thousand such killings take place in India, the land which taught world how to love, which accepted all coming to the holy land and embraced all religion, caste and race at the first opportunity. «They have so much strength that this can help them to survive». When they leave, the women firstly get hidden, they avoid any type of public service such as the NHS (National Hospital Service), and they may get a low profile job. «They almost become invisible members of the society. They may have to move several times to keep safe» because the threat of being discovered by their family or recognized by members of their community is real. Consequently, trust is a crucial factor to motivate the survival women to come forward and look for help.

The Sharan project deals with approximately 500 cases every year, 90 percent of which bring up elements of honour-based abuse. The majority of women who get help from the charity come to the realization that their issues are not isolated, and they are not alone. Others like them, who come from strict families, experience the same. They are forced to live a double lifestyle, which develops into a «split personality». The split personality has to cope with the repressive and submissive family environment and, on the other hand, the openness of a society that offers opportunities for each individual to achieve their own goals and accomplishment of their self-realisation. Mumtaz’sThe book, I hope would prevent further honour killings. story shows how disowned women can still realise their dreams despite their family’s hostility. Mumtaz was rejected by her family for pursuing her career. Eventually, she became a successful artist and got married with two children. When she left home for cultural reasons, she was surprised to see that the Sharan project was the right organization to deal with her case without using any label, biases or cultural ignorance, «I fell as if I have found my true voice through Sharan». Tina’s story is another classic story of a young woman of 19 years old who agreed to an arranged marriage. After a period of positive cohabitation, the husband became violent towards Tina, and his aggressions and beatings increased. She finally filed for a divorce but the family disapproved her action. They felt the daughter brought shame to the family name and disowned her. She was also outcasted by the community and so decided to leave and start a new life, thanks to the guidelines of the Sharan Project [19].

These are some of the stories that the charity shares on its website. The stories also serve to tackle with this type of cultural tradition and redressed it. How can it be done? Polly firmly believes that changes can happen through engaging in frequent conversations in public and worshipping areas within the community at high risk of honour-based abuse and make the members of the community understand that violence against women is wrong, immoral. Furthermore, it is essential to work with those families who genuinely think that killing a female family member is right. This type of mentality must be changed. «Education is key, and we must educate boys and girls» as well as old generations, and we must help the community to open itself to a real integration within the British society and culture to avoid ghettoization.

Dialoghi Mediterranei, n.31, maggio 2018

Abstract

Dopo oltre 30 anni, il fenomeno dei crimini d’onore contro le donne è riapparso nella società occidentale minacciando i suoi stessi valori umani, come è accaduto nel Regno Unito, con i tanti omicidi di donne provenienti da famiglie di immigrati dal Medio Oriente e dal Sudest asiatico. Nonostante le donne musulmane siano le più esposte a tale detestabile fenomeno, questo non significa che il crimine d’onore sia una pratica esclusiva della cultura musulmana. La storia dimostra che le donne sono state uccise per onore fin dai tempi più remoti. Le ragioni che portano a tale gesto estremo sono molteplici, in primo luogo c’è l’umiliazione che la famiglia di appartenenza percepisce quando una figlia, una cognata o sorella assumono comportamenti non consoni con le norme di una cultura fortemente patriarcale, in cui i ruoli dell’uomo e della donna sono ben definiti. E non sono consentite trasgressioni.

Sul fronte dei diritti umani molto si è cercato di fare da quando è stato istituito il trattato internazionale sui diritti delle donne, conosciuto come Convenzione sulla eliminazione di ogni forma di discriminazione contro le Donne (CEDAW). Lo scopo del trattato è quello di proteggere le donne da qualsiasi forma di violenza derivante anche da pratiche tradizionali e culturali. A tale riguardo la Commissione sul CEDAW ha adottato la raccomandazione Generale n°19 per rimuovere dalla legislazione la cultura di difesa per giustificare casi di crimini d’onore. Questo è stato nuovamente ribadito nel luglio dell’anno scorso.

Ci sono stati casi nelle Corti Inglesi in cui i colpevoli si sono avvalsi della difesa della loro cultura in senso antropologico per giustificare i loro crimini. Questo tipo di difesa non può essere accettata perché i crimini d’onore devono essere considerati, a tutti gli effetti, violazione dei diritti umani contro le donne. Il Regno Unito è il Paese più sicuro per le donne, secondo l’opinione di Polly Harrar, fondatrice di Sharan Project. Il Charity si occupa di aiutare le donne che sono state abusate e respinte dalle loro famiglie, perché considerate causa di disonore e vergogna anche per la stessa comunità. Per poter ridurre tale fenomeno, bisogna rivalutare le tradizioni culturali, come Polly sostiene. È importante che le comunità con una forte tradizione patriarcale si aprano al dialogo per evitare l’isolamento.

L’ultima parte del contributo tratta di un caso di crimine d’onore inflitto ad una indo-canadese, Jaswinder Kaur, “Jassi” Sidhu, nel maggio del 2000, quando si recò in India, nel Punjab, per incontrarsi con il suo amato, Su Khiwinder Singh Sidhu (chiamato Mithu), il quale l’ha sposata segretamente contro la volontà della famiglia. La madre e lo zio hanno ingaggiato dei sicari per uccidere Jassi vicino Ludhiana. Il caso è stato portato all’attenzione dei media grazie alla pubblicazione di un libro Justice for Jassi, scritto da Jupinderjit Singh, giornalista indiano al “Tribune di Chandigarh”, con la collaborazione di Fabian Dawson ed Harinder Singh Sewak.

Note

[1] A/HRC/20/16/Add.4. General Assembly. Distr.: General. 16 May 2012. (Accessed 17 March 2018)

[2] Stewart Charles, Honor and Shame, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/anthropology/people/academic-teaching-staff/charles-stewart/Honor_and_Shame–2013__Stewart.pdf.(Accessed 17 March 2018)

[3] AbdelhadiWafaa, Honour. Honour Crimes and Violence against women, http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=139874. (Accessed 17 March 2018)

[4] Ibid.

[5] Stewart, Honour and Shame: 13.

[6] Olwan M. Dana, Gendered Violence, cultural otherness, and honour crimes in Canadian national logics: 539 https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/cjs/index.php/CJS/article/view/21196 (Accessed 17 March 2018)

[7] Idriss Mohmammad Mazher, Not domestic violence or cultural tradition: is honour-based violence distinct from domestic violence?www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09649069.2016.1272755 (Accessed 17 March 2018)

[8] Olwan Dana

[9] Idriss Mazher: 4.

[10] Ibid: 13.

[11] UN News Centre, https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/06/558972-gender-based-killings-domestic-violence-forms-arbitrary-execution-un-rights. (Accessed 17 March 2018)

http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session35/Pages/ListReports.aspx Document: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session35/Pages/ListReports.aspxA/HRC/35/23. (Accessed 17 March 2018)

Document: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session35/Pages/ListReports.aspxA/HRC/35/23. (Accessed 17 March 2018)

[12] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Preamble http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/. (Accessed 17 March 2018)

[13] United Nations Women Topic 1: Honor Killings Topic 2 – DMUNC, http://dmunc.org/wp-content/uploads/UN-Women-Topic-Guide-Final-Formatted.pdf. (Accessed 10 April 2018)

[14] Abdelhadi Wafaa, Honour. Honour Crimes and Violence against women. http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=139874. ( accessed 17 March 2018): 25; UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), General Recommendation No. 19.

[15] Abdheladi Wafaa: 30

[16] Nootash Keyhani, Honour Crimes as Gender-based violence in the UK: A Critical Assessment.http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1470686/1/2UCLJLJ255%20-%20Honour%20Crimes.pdf.( Accessed 17 March 2018), p. 269.

[17] International day on the Elimination of Violence against Women, 25 November. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22432&LangID=E( Accessed10 April 2018)

[18] General Recommendation No.35, III: 21.

http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/1_Global/CEDAW_C_GC_35_8267_E.pdf.

[19] Sharan Project , http://www.sharan.org.uk/., Case Stories. (Accessed 21 April 2018

________________________________________________________________________________

Paola Barbuzzi, laureatasi in filosofia all’Università di Bologna, dopo qualche anno di insegnamento di L2 a donne migranti, si è trasferita a Londra per frequentare dei master sui diritti umani e la medicalizzazione del corpo femminile. Stabilitasi da oltre un decennio nella capitale britannica, lavora con `NGOs sulla difesa dei diritti umani e la loro violazione, in modo specifico, sulle donne.

Jupinderjit Singh, giornalista che lavora per Tribune, Chandigarh, ha scritto in collaborazione con Fabian Dawson Jastice for Jassi. Recentemente ha pubblicato un libro di storia, Discovery of Bhagat Singh’s and his Ahmisa.

________________________________________________________________________________

I am very impressed by this article even if, since ages, I have known of these crimes because of my friendship with many Indians and Pakistanis. I wonder when they will realize that killing a woman for honor is a crime against Allah or other Indian gods. The principles of compassion and humanity are common in every faith. In most case these crimes are in rural areas of these countries, where education doesn’t exist, where schools can be only for boys cause girls are considered only a good to exchange with cows. Congratulations you did a wonderful job. Go on like this

Thank you for drawing our attention to these issues – never to be forgotten. You did a great job – a fine and precise research.

As Linda Edvardsson states in her Bacchelor Thesis at Malmö University,

Department of International Migration and Ethnic Relations, “Crimes of Honour” (2008): “Some females live in constant fear. They live in constant fear because they could have their spying brother as their worst enemy, their mother as a tyrant and their father’s honour depending on how they behave socially. These females ought to obey the norm that exists otherwise she could be forced to marriage someone, abused or murdered”.

This has to be over – all over the world.